To do her research, Whitehead is documenting the COVID-19 imprint on the nation’s psyche through multiple media sources; while, at the same time, examining the effect of the pandemic on older adults through time-limited surveys following historic markers such as Michigan’s Shelter-in-Place order and the approval of the Coronavirus Stimulus Package. The Time 2 survey is available to take through 3 p.m. Tuesday, March 31. Any U.S. adult aged 60 or older can participate.

“The reality is that perceptions and behaviors are going to shift as this event unfolds, so I am looking to map older adults’ experiences onto what is happening in the U.S. at a given moment as it relates to COVID-19.”

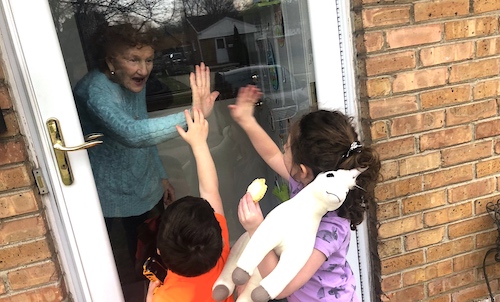

She’s spotting trends — it’s too soon to share most — but there’s one she wants to get out now as a call-to-action for younger, able-bodied people: “Our brains are not wired to handle social isolation. Please find ways to spread joy to your neighbors or family members who are older adults. There are ways to do this and still maintain social distance.”

Here are some examples:

• When on a walk, wave at people you see on the porch or in their windows.

• Write positive messages with sidewalk chalk — it can be as simple as ‘Good Morning’ — on their front walkway or on the sidewalk in front of their homes.

• Visit through the window. If there is an open window nearby (but make sure it’s a socially safe distance away), you can both have a conversation.

• Make that phone call.

• If you don’t know their phone number, send a letter or card.

• For the older adults in your life who are tech savvy, use teleconferencing, social media or send emails.

• Kids love crafts. If you have children at home, encourage them to draw pictures or make signs for your windows that people can see when walking. If there is lettering on it, make the letters larger so it is easier for all to read.

• Talk about the future. When communicating with your older loved ones, don’t just dwell on COVID-19 — although talking about it is fine — also mention what you are looking forward to with the person once social distancing ends.

Whitehead says many older adult survey participants have mentioned ways they try to create connections — for example, one woman puts stuffed animals in her windows to stand out from the other homes to people walking by. “People are experiencing this time in very different ways. Many have had positive things to say; the majority of those happy stories included forms of social interaction.”

Whitehead says her survey is a combination of closed-ended and open-ended questions; the open-ended questions allow participants to share their experience in their own voice disentangled from researcher assumptions. For example, one asks: “What are some older adults doing to successfully manage the stress, and how can we help spread those successful approaches to others?”

Whitehead says the Time 2 survey takes about 15 minutes to complete and, at its core, is about discovering what is stressful about this time and exploring how people are able to maintain positive well-being even in the midst of the stress.

“The reality is that, right now, no one knows exactly what will happen or how long this will last--we haven’t experienced something to this scale in our lifetimes. By documenting the experiences of older adults and identifying factors that promote mental health during population-level stressors like this, we as a society can be more equipped to support those aging around us, both now and during future events.”

Whitehead plans to share preliminary research outcomes on her website at the end of April.