If mutant hens are the focus of your research, be ready for playful comments from friends and colleagues.

“They always expect that they must look like mutants, or that they’re boneless chickens or something,” said Marilee Benore. The professor of biochemistry and biology in the Natural Sciences Department in the College of Arts, Sciences, and Letters (CASL) is heading the study.

The flock of 40 white leghorn chickens from Pennsylvania, housed at Michigan State University, looks normal. But when cracked open, the hens’ egg whites run clear rather than yellow. The crucial vitamin riboflavin is missing, so the eggs do not hatch.

The study at University of Michigan-Dearborn seeks to build understanding of how chickens and other animals absorb vitamins and other chemicals, to impact body processes.

“It also would help us to understand how molecules are delivered specifically to tissues and organs, to help us design better drugs that have fewer side effects,” Benore said.

A key job before Benore and her team of UM-Dearborn CASL research partners—faculty John Abramyan, Simona Marincean and Sheila Smith—is to develop a diagnostic test of how the vitamin riboflavin impacts embryo development.

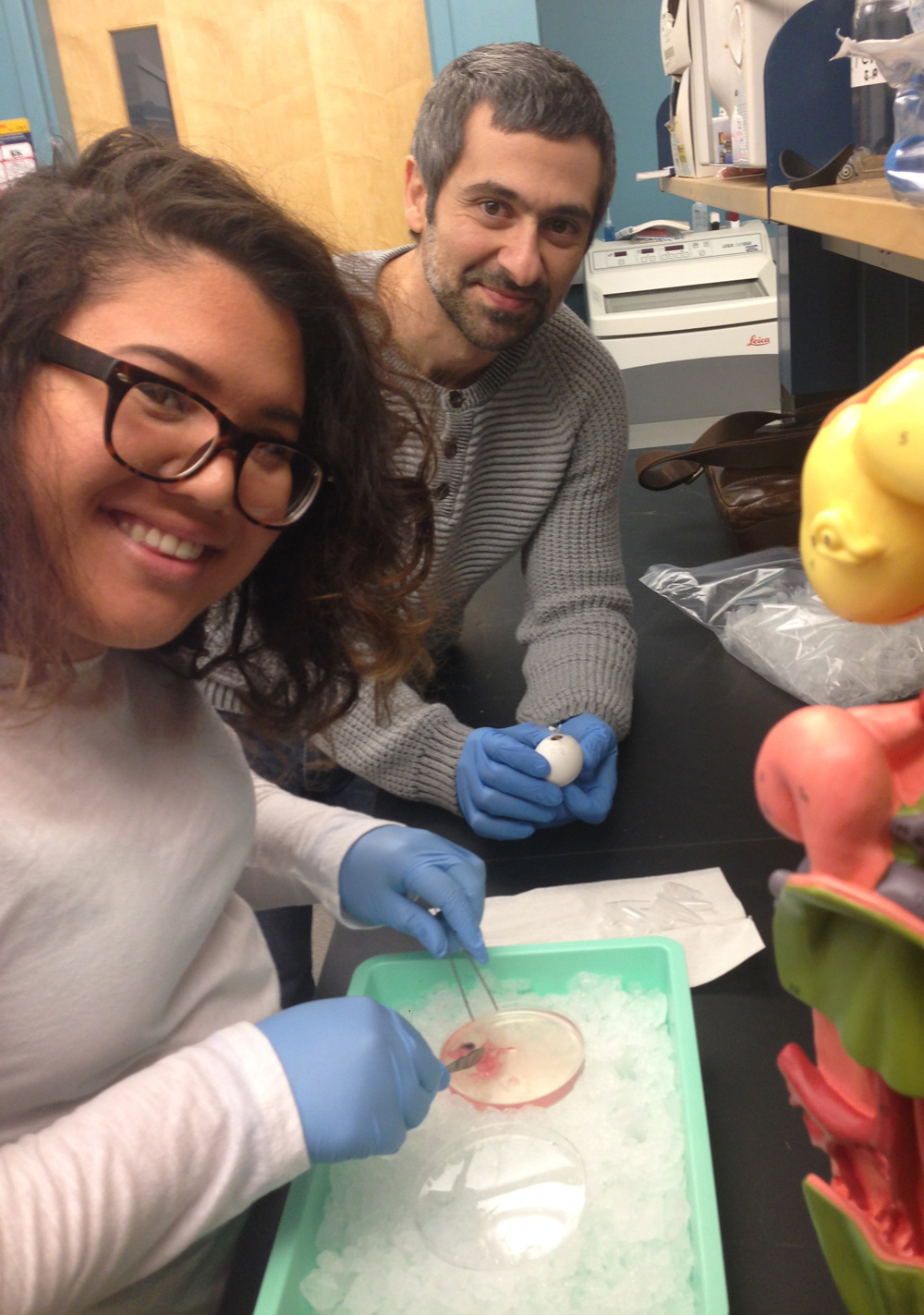

The researchers, aided by several undergraduate assistants, also are looking for other possible genetic mutations in the flock.

Benore first studied the mutant hens as a research assistant at University of Delaware, with Professor Harold White in the 1980s. Benore took the project over in 2011. She has since enlisted Abramyan, assistant professor of biology, and Marincean and Smith, both associate professors of physical sciences.

Marincean studies ways to measure the vitamin more accurately by creating a diagnostic test for measuring riboflavin using a riboflavin binding protein. Smith is a metals expert, researching copper bound to the eggs. It is one of the minerals required for metabolic processes. Abramyan is an expert in embryos.

“We intend to look at the shape and structure of the entire embryo using micro-CT scanning, to see if anything is malformed,” Abramyan said, and to examine the cellular structures of other tissues for defects. “This could potentially give us an insight into human development, and in particular how riboflavin deficiency during pregnancy may effect the developing baby.”

The researchers don’t visit the flock to avoid needless contamination. “We’re really focused on the eggs themselves and the development of the embryos,” Benore said, adding that they also are purifying the protein from normal eggs. “We have a perfect model system because we have chickens that are normal and we can compare them to these mutants that don’t make the protein.”

The best thing about the project is its relevance and significance, Benore said. “I also love that undergraduates can work on this project with me.”

Jessica Vo is a biology student working on the project. “It's great to see the mutant embryo develop and see how the mutation affects the morphology of the chick. It's also really interesting to be able to isolate the sequences that are responsible for the mutation,” she said.

Biochemistry student Quintin Solano said working on the project allows for students to grow professionally as academics and researchers. “Students, upon graduation, are expected to be able to perform fluently in research lab settings as well as computational research settings,” he said. “This project allows for students to grow in both of those aspects, all while gaining advanced critical thinking and lab skills that are invaluable in the ever growing world of research we live in today.”