Just like many of us, Kate Truitt gets daily emails that include discussion threads, meeting times and inquiries looking for a consensus on what to do next.

But the UM-Dearborn sophomore’s messages are from NASA—about Mars exploration.

Truitt, through Geology Assistant Professor Mark Salvatore, is part of the research team on the latest mission to the Red Planet: the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) Curiosity rover, the first nuclear powered, Humvee-sized robotic vehicle on Mars.

“I’ve been fascinated with astronomy since I was in third grade and, on a family vacation to Yosemite, my dad had us look at the night sky. We could see so many stars. I got a feeling about how small we are in the universe—Earth is just one part of the big picture,” said Truitt, an Earth Sciences major. “Now I’m part of a team that is on the front lines gathering data to see other parts of the picture. It’s amazing.”

Salvatore, who serves as Truitt’s adviser, asked Truitt to join the team and to assist in his research endeavors after teaching her in his Remote Sensing class and seeing her excitement over the topic.

Salvatore was selected as a participating scientist on the MSL project earlier this year, joining a team of 27 other participating scientists and nearly 300 additional scientists and investigators. His first contributions to the mission date back to 2007, when he was an undergraduate intern helping to map candidate landing sites for the mission at the Lunar and Planetary Institute and NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. The mission launched in 2011, landed in 2012 and has been exploring the Martian surface ever since.

“Missions like these are essential. They can show what makes Earth unique and what makes Earth and Mars very similar,” said Salvatore, who said four different rover missions have been active on Mars over the past 20 years, with the hope that each new mission advances information to allow for eventual human exploration. “So if we find that there was life on Mars and it evolved and went extinct—that means that there are two confirmed spots in the same solar system where life has evolved. Then you ask: What are the odds that with 100 billion stars in our galaxy, and the 100 billion galaxies out there, that life didn’t evolve somewhere else too?”

In addition to contributing to NASA’s overall mission of the Curiosity rover—which is to study the planet’s climate and geology and see if Mars could have sustained life—Salvatore has his own geology-based research question: How do rocks alter in the martian environment and can we compare these processes to the alteration of rocks in the cold and dry Antarctic environment?

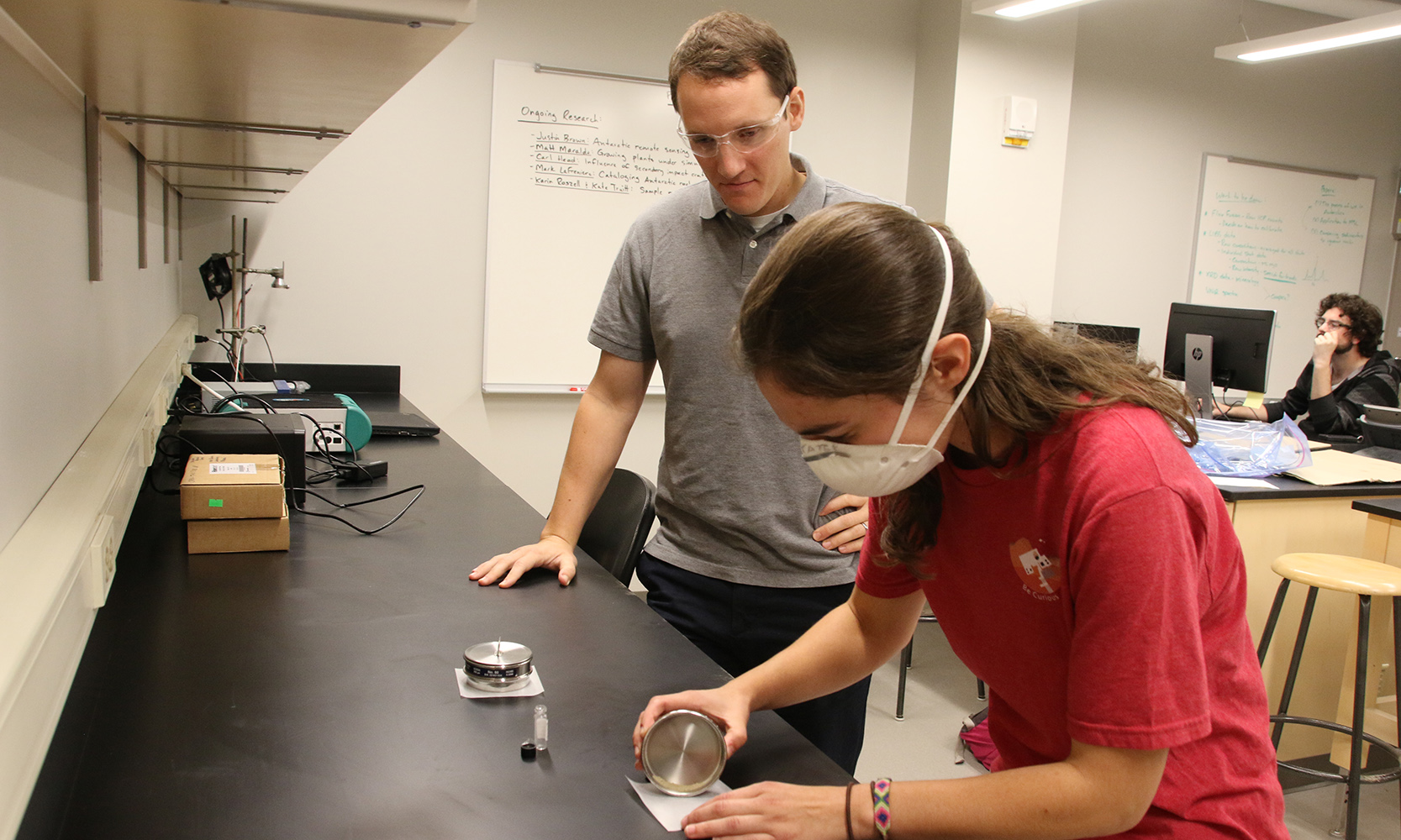

Truitt is helping assist him with this research, along with junior Mark LaFreniere and post-baccalaureate researcher Karin Roszell.

In Salvatore’s Natural Sciences Building-based lab, the students look at rocks collected from excursions to Antarctica, prepare them for analysis, and measure their chemical composition. They will eventually take these findings and compare them to the samples the Curiosity rover is currently analyzing on Mars’ surface.

“I can’t believe I get to do this at 19,” Truitt said. “I’m so glad that I came to UM-Dearborn. This is a place where the professors know you well enough to recognize what you are interested in, and then reach out to you to get you involved.”

Salvatore said he understands, from personal experience, the positive effects of undergraduate research.

“My first foray into planetary science came when I was an undergraduate student. I had a faculty member who got me involved with research early,” Salvatore said. “It helped me get an internship at NASA, get into graduate school and set me on a course that I otherwise might not have traveled down. I want to provide my students with the same opportunities.”

The next Mars rover launch is scheduled for 2020, and Salvatore already is involved in the planning stages for that endeavor as well.

“At the moment, it looks like we’ll be able to send humans to Mars in our lifetime; NASA is hoping to do so between 2030 and 2040,” Salvatore said. “And it’s nice—even if it is very tangential—to contribute to that, even if it is just laying some of the initial scientific groundwork. “

And Truitt said she’s looking forward to working with Salvatore on this research project for the next few years and adding her own contributions as well.

“It will be interesting to see what the data brings back, to learn of the similarities and differences of Earth and Mars. At this point we don’t know. But soon there is going to be so much data there available and I’ll get to be a part of the team who discovers it,” she said. “I think we all want to make a mark on history and to make a difference. Doing research for this mission may be my way to do that.”