Even when you leave a place, it stays with you.

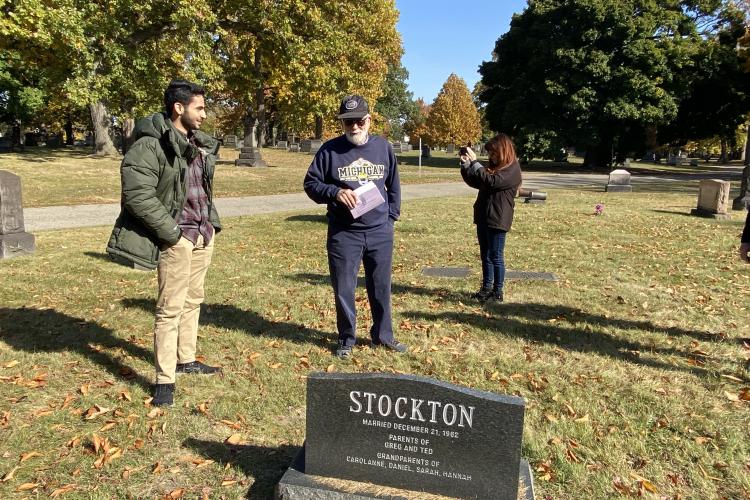

Across the cemetery, there are national flags from across the world, flora and fauna specific to a place, holy book etchings and more. Stockton said even when people move from one place to another, what represents home stays with you.

Stockton showed the class where his marker is at Woodmere. It has the image of a dogwood bloom on it — a tree that’s native to Illinois, his home state.

Albanian headstones often show an ancient Byzantine Christian symbol of a two-headed eagle facing east and west, alongside a photo etching of an Islamic one, an Albanian mosque. Why both? “This is a people with a lot of history. Albanian identity came first, before culture and religion evolved over hundreds of years with changing leadership. During the long Communist era, this mosque served as a symbol of continuing Albanian identity. Among these Albanian graves, we see that national or ethnic identity often supersedes religious identity, or at least persists alongside it.”

There’s also a grave in the Islamic Sunni section of the cemetery that includes a heartfelt poem in Arabic that Abdallah Berry, aged 100, wrote. It was about longing for his Lebanese homeland and wanting to smell the flowers and feel the soil — but being unable to return, even in death.

Honors Program freshman Sara Moughni said the poem was sad, but touching. And she was honored to read what Mr. Berry left as part of his legacy.

As the students left Woodmere, they kept thinking about the place they just experienced — so in a way, the cemetery was a place that stayed with them.

“I walked in with a preconceived notion that cemeteries weren’t places that I’d want to visit because I did not want to be surrounded by death,” Moughni said. “Dr. Stockton showed us that cemeteries are actually full of lives lived and people representing themselves through inscriptions to share their histories with us. It’s beautiful to see so many people from different backgrounds, places and beliefs together all in one place.”

Article by Sarah Tuxbury. Below are additional images of markers at Woodmere Cemetery. Thank you to Assistant Director for Research Administration Pat Turnball for your photos.