This article was originally published on October 20, 2021.

The Andes are the longest mountain range in the world. Its floor touches the Amazon Rainforest. And, located within them, are large bodies of ice that are strikingly beautiful and provide an important natural resource.

Earth and Environment Professor Ulrich Kamp, a 30-year glaciologist, has hiked in the Andes and has seen the Quelccaya Ice Cap, located in the Andes. He knows how important the ice masses are to the Peruvian fresh water supply during the dry season. But in the 17 years since Kamp first saw glaciers in the Andes, there have been environmental changes.

In recent years, Quelccaya went from the largest to the second largest tropical body of ice — and climate models predict that without mitigation measures, Quelccaya is likely to disappear within the next century...and some say in the next 35 years.

“Unfortunately, some local communities and regional authorities welcome the additional meltwater — but it often also means flooding. In some places, irrigation and agricultural systems that have worked for decades, or even hundreds of years, have been destroyed by the excess water,” Kamp said. “But in the near future, the meltwater runoff will cease. Once the glacier recedes to the summit, its highest and coldest part, the melt stops and, with it, the meltwater flow. Entire communities might lose their main natural water resource. It will be devastating.”

After Kamp — an active researcher who has monitored glaciers in India, Mongolia, Pakistan, Afghanistan and other parts of the world — gave a lecture about his research at Vanderbilt University in 2018, an archaeologist in the audience approached him to discuss a 1931 photo taken of the Vilcanota Range, located in the Andes Mountains.

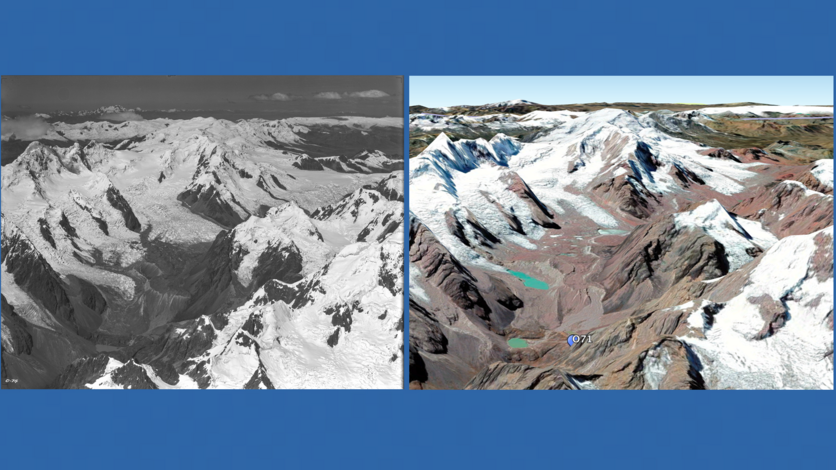

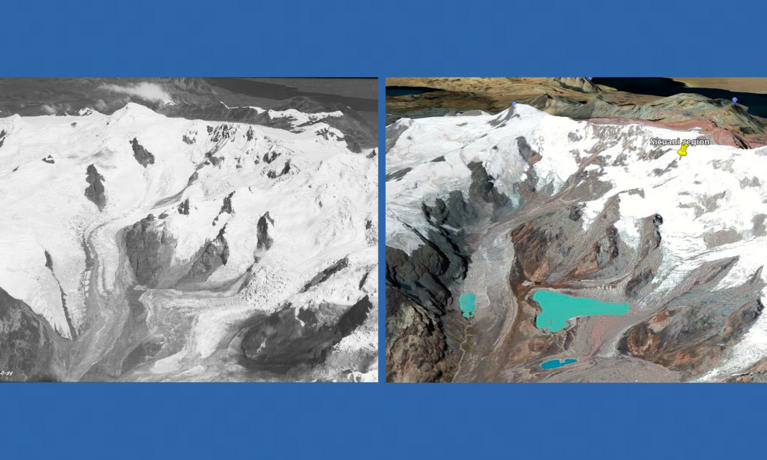

It was a black and white aerial picture from an exploratory expedition by Harvard University geologist Robert Shippee and pioneer aerial photographer Robert Johnson that showed what the Vilcanota glaciers looked like only five years after Charles Lindbergh completed the first solo nonstop transatlantic flight.

“Heritage photographs are a treasure trove for modern researchers concerned with landscape change analysis. I couldn’t believe that there was an aerial image of these glaciers from 1931. The photo was sharp and good quality — and I learned there were more at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH),” he said. “I wanted to be the glaciologist to research those pictures.”

Kamp’s glacial imagery research is one of nine projects highlighted in the College of Arts, Sciences, & Letters Annual Faculty Research Slam. The event, where professors give seven-minute abstracts of their work, takes place at 3 p.m. Oct. 28 via Zoom.

Kamp said he wanted to participate in the event to bring our global impact to the forefront. “There is so much beauty in nature that needs our protection.”

Knowing the power of documentary photography, Kamp traveled to the AMNH in New York to view and digitize photos from the collection. There were 3600 photographs to sift through, 400 containing glacial images.

During the eight-month National Geographic Society-endorsed Shippee-Johnson Peruvian Expedition of 1931, the two men flew Bellanca Peacemaker monoplanes and planned to capture images of archaeological sites like the Great Wall of Peru and the Incan citadel of Machu Picchu. But they also inadvertently documented the ice masses prior to major effects of industrialization. “They accidentally came upon them,” Kamp said.

Kamp’s goal is to map the plane’s flight path and compare the heritage photos to more current imagery. However, because no data came with the images like the plane’s flight altitude or photo-shooting direction, this is a difficult task. Graduate students Elise Arnett and Renato Marimon are helping Kamp recreate the flight path by checking the physical photos against satellite images on Google Earth.

“We have made progress on this. Using satellite images, our preliminary results from three sites document recessions at individual glaciers of up to 94% since 1931,” Kamp said.

The plan is to travel to Peru in the next year and conduct fieldwork where Kamp and the team of this National Geographic Society-funded project will take 45-degree angle images from an airplane and a drone. Then, using 90 years of imagery, he will visually show the glacial recession. Kamp is currently seeking additional interested UM-Dearborn students to assist him in this research.

The project team will create a traveling exhibit of the timelapsed imagery, once the research work is completed, and will make both the old and new images publicly available and searchable online.

“I can write pages and pages of publications about cubic kilometers of ice disappearing rapidly, but that doesn’t have the same effect as showing someone what that looks like,” he said. “When you see this impressive ice mass shrinking, the information stays with you.”

Kamp hopes that showing the effects of climate change will encourage behavior and habit changes like driving less, using energy more efficiently, and slowing down consumption. Quoting his favorite explorer Alexander von Humboldt, Kamp said, “Everything is interconnected.”

“The Peruvians are being impacted by emissions produced from the northern hemisphere. What we do here, doesn’t just stay here. It impacts the quality of life of people around the world. Almost two billion people rely on water from glacial meltwater.”

Kamp shares his research in campus courses and through getting students involved with research. Seeing the advocacy and environmental justice efforts by his students, Kamp said change may come before the damage is irreversible.

“They are angry that these environmental changes have been relatively ignored, but are channeling that anger through something positive — advocacy,” he said. “Sometimes it’s difficult to know what we can do with a huge message like changing a culture of comfort and consumption. My advice is to learn from the information we now have and teach the next generation to do better than we did. That is where the hope lies.”

Kamp’s research projects connected with the Shippee-Johnson Peruvian Expedition of 1931 are in collaboration with Indiana State University, Stony Brook University, Vanderbilt University, and the U.S. Geological Survey agency.

If you are a UM-Dearborn student interested in Professor Kamp’s research, please contact him at ukamp@umich.edu. If you are involved with a media outlet that wants to learn more about this research, drop us a line at UMDearborn-News@umich.edu. Article by Sarah Tuxbury.