Healthy Dearborn—a community coalition anchored by Beaumont Health, the City of Dearborn and Dearborn Public Schools—may only be a few years old. But its 500-plus members already have racked up an impressive list of victories—including a new bike share project, multiple community fitness programs, improvements to the local farmers market and a robust research team that’s providing data-driven insight into the health needs of Dearborn residents.

The goal is to build a holistic “culture of the health” in the city by improving access to healthy foods and supporting active lifestyles. But as Healthy Dearborn forges ahead, steering committee member and UM-Dearborn Sociology Professor Carmel Price said there’s a renewed emphasis on ensuring the coalition’s work is addressing health priorities for all—and not just some—of Dearborn’s residents.

“The challenge we recognized is that the people who are shaping the conversations are often those who already have more resources,” Price said. “But what about the parts of the city where there are higher rates of chronic conditions? Do they have representation in the Healthy Dearborn coalition? Are they included in the conversations that shape policy and programs? We didn’t want all this great work we’re doing to reinforce the inequities that exist.”

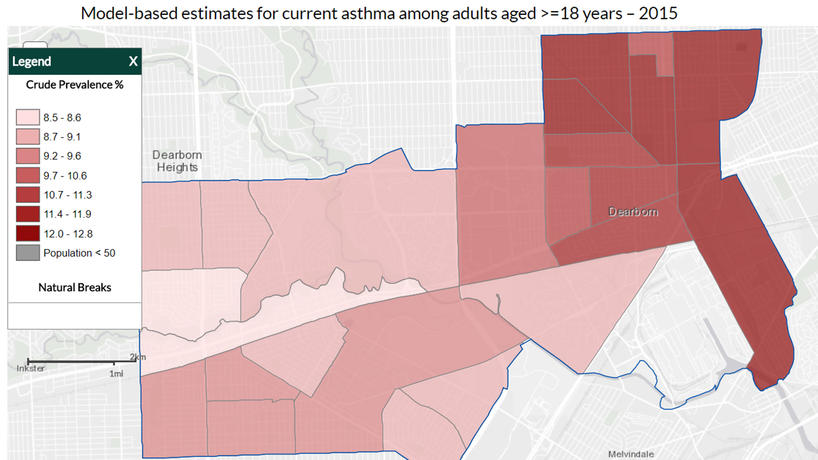

While health disparities have always been part of the Healthy Dearborn mission, Price said it’s become a higher priority since the release of new health data from the Centers for Disease Control. The CDC’s 500 Cities project, detailing chronic disease risk factors and health outcomes in America’s 500 largest cities, painted a picture of a heterogeneous community, where some neighborhoods had far different health outcomes than others. Among the major storylines revealed in the data: Residents in east and south side neighborhoods, which border some of the heaviest industry in metro Detroit, had higher rates of asthma and COPD than their west side neighbors.

New health data from the Centers for Disease Control shows residents in east and south side neighborhoods had higher rates of asthma and COPD than their west side neighbors.

“When we typically think about healthy living, we think about exercising more or eating better,” Price said. “But when we held some community forums on the south side, the resounding message from residents was that their biggest need was air quality—and the fact they didn’t feel comfortable being active outside because of air quality. So it was a much different set of challenges that require a different kind of work than the coalition had done so far.”

Price’s good friend and UM-Dearborn colleague Natalie Sampson has been crucial in that work on the south side of the city. The assistant professor of public health and veteran of air quality campaigns in neighboring Detroit also has enlisted students in one of her public health courses to help facilitate community forums. Sampson said some students, like Karima Alwisha, a south Dearborn resident and public health major, have emerged as strong community leaders.

That work has inspired what Sampson calls “a separate but closely related” new initiative called Environmental Health Research to Action (EHRA). Through EHRA, Sampson, her students, Price, and key community leaders and partners are undertaking several new projects around air pollution, including building an air quality report for the city and launching a summer youth academy.

“The idea is to not just get youth to understand air quality issues—they live there, they know all about that,” Sampson said. “But we can help train them in the science, the epidemiology, how to do air monitoring—and how you can then take that and create a policy advocacy strategy.”

This semester, students in Sampson’s Community Organizing for Health course also worked on so-called “shared use policies.”

“Given that there’s interest in physical activity, but people can’t always be active outside, Healthy Dearborn is trying to make sure people have access to indoor public spaces, like high school gyms, after hours, for exercise,” Sampson said. “So students are researching existing resources and policies and what other communities have done to see if this makes sense for Dearborn.”

Sampson and Price said creative solutions like these are indicative of the contributions the UM-Dearborn community is making in the push to make the city a healthier place. In all, more than 50 faculty, staff and students have lent their effort and expertise to various Healthy Dearborn coalition projects.

“Our students are a critical piece of getting this work done,” Price said. “The coalition members are developing strategic plans and action plans, but when it comes to implementation, we’ve really relied on students to make these ideas a reality. And our researchers—here and at Wayne State and elsewhere—are writing grants, doing data collection, and providing all kinds of expertise. So it’s incredibly exciting to see us building momentum.”