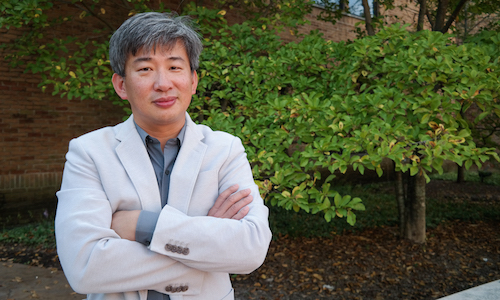

Decision Science Assistant Professor Wayne Fu pulls up an article on his computer, “Astronomical PFAS level sets new Michigan contamination milestone.” He recaps that the cancer-causing toxin is present in Michigan’s surface water. It’s 450 times what the state allows and 78 times the lifetime health advisory for human consumption.

With Fu’s interest and expertise in industrial and environmental practices — prior to academia, he worked in supply chain management as a solution architect for after-market services, helping find rejuvenated uses for discarded or used items — he will be following this closely.

“People wanted products produced faster at lower prices. With plastics and other chemically created materials, it could be done. But there’s an unforeseen cost, and we are seeing it more and more. This is a consequence to not understanding the innovation that came about in the mid-20th century,” said Fu, who mentioned that PFAS was first included on the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry’s (ATSDR) Substance Priority List (SPL) in 2017.

That list ranks 275 substances that are a threat to human health by taking into account both the relative toxicity of the chemicals as well as how likely they are to come into contact with humans. It is subscribed to by more than 56,000 email accounts — many tied to industrial facilities — and notifications are sent when a new rankings list is published.

Through findings in his recently published research — “Are Hazardous Substance Rankings Effective?”— Fu believes there will be improvement. The research looked at nearly a decade of information and has seen that business production practices do change with updated information and improved awareness. Even when regulation doesn’t require it.

“Of course, regulation is important. But this study shows that information — from credible sources — has an effect on behavior too,” he said.

Looking at data from 2001-2009, Fu — with co-researchers from Georgia Institute of Technology — examined the ATSDR’s SPL and the Environmental Protection Agency’s annual Toxics Release Inventory, which tracks the emissions of more than 20,000 facilities across the country. Fu and his team found that once a chemical’s rank moved up on the SPL, there was a substantial reduction on the subsequently reported emissions.

“A reduction of four percent on average. This is not law driven, this is information driven,” said Fu, who visited the ATSDR facility in Atlanta to learn how they tested, classified and ranked the toxins. “Looking at changes over time, the study strongly suggests that companies are concerned about occurrences like these and when information is shared that there are hazardous chemicals in production.”

Fu said the research study shows a pattern of toxin reduction based on their assessed hazard levels, but it doesn't show why the changes were made. He speculates that employee liability, public relations or cleanup costs may be among the reasons. Or it could simply be a lack of information. But, to Fu, the important part is that there is evidence that shows a reduction in toxic output when the information is presented.

And since the study shows a strong relationship between information and action, Fu believes next steps may include educating managers prior to needed cleanups — as in the current PFAS case, which was outside of his research timeframe — or emerging health crises.

“This opens the door for continued research on how education can help companies become more proactive and less reactive — while still meeting increasing consumer demands, improving operational efficiency and being socially responsible,” he said. “If people are properly informed , I believe people will do the right thing.”