This article was originally published on October 14, 2019.

Ever wonder why people who are in difficult situations may have difficulty in making choices that could lead to more opportunity?

Assistant Professor Jessica K. Camp gives an answer: Trauma. The College of Education, Health, and Human Services educator says trauma exposure has the ability to physically change our brain and influence our cognition, particularly in the area responsible for emotional recognition, emotional regulation, empathy, decision making, and many other skills necessary for maintaining relationships and connections.

“So when we might wonder why someone who has repeatedly experienced trauma makes a choice that doesn’t align with their best interest, makes a decision that leads to a negative life outcome, or disconnects from important life opportunities or experiences, this may be the answer,” says Camp projecting a PET scan of a brain affected by trauma, showing diminished neuronal activity in the cortex of the frontal lobe.

Knowing this, what are the next steps?

Camp, along with other researchers, are combining discoveries like the neurobiological impact with an understanding of trauma exposure from medical, healthcare, psychology, and social work fields and are working to figure out what events are important to consider when examining the connection between trauma exposure and adverse outcomes in adulthood.

Helping lead the way in the area of trauma recovery, Camp is finding success with an approach that teaches others how to view trauma through a Trauma-Informed Care and Restorative Practice lens — Healing Centered Restorative Engagement (HCRE). This approach encourages people to recognize the impact of trauma exposure as a disconnecting force from life opportunities that are critical for attaining well-being.

“Many systems punish through exclusion, if you show up for work late you may lose your job, act out in high school and you may be suspended, do poorly in a college course and drop the class or lose critical financial aid,” Camp says. “What if, instead of excluding as a punishment we reformed systems to be inclusive as support?”

She gives another example to show how re-phrasing can still get the message across, but use the HCRE approach to ensure the problem outcome is identified as the problem, rather than making the person feel like a problem.

“For example, if someone is late, instead of harshly saying, ‘You’re late. What’s wrong with you?’, ask, ‘What happened today? Let’s talk about it.’ It’s still important to hold people accountable, but you can do it in a way that helps find solutions to problems. That’s what’s best for everyone involved,” Camp says. “Trauma survivors will be more sensitive to feelings of threat and lack of belonging, as the brain has been developed to be amazing at ‘survive’ at the cost of ‘thrive.’”

For the record, Camp’s not discounting the traditional model of trauma-informed care. But with the large number of people in need, it doesn’t always work as intended — the approach is reactive instead of proactive and it is only engaged once a problem has been clearly defined.

With trauma so widespread, there aren’t enough specialists available to handle the demand. By creating systems that heal and include, there is more of an opportunity to create pathways to recovery, facilitate resiliency, and include people in their future well-being.

“Healing Centered Restorative Engagement is something everyone can practice or can be trained to practice,” Camp says. “It’s not about diagnosing a problem — after all, most of us don’t have access to PET scan imaging or the credentials to diagnose. Rather, it’s an empathetic approach that can be used to build stronger connections in an effort to build relationships, trust and feelings of belonging: All are healing practices associated with trauma recovery.”

With the prevalence of trauma, its impact on society — for example, there’s a $2 trillion lifetime cost when looking at the impact of only one type of trauma, childhood maltreatment, on the U.S. economy, according to 2018 research done by the National Center for Injury Prevention — and the promising antidotal evidence of healing and recovery with this new approach, Camp, along with Office of Metropolitan Impact (OMI) Executive Director Tracy Hall and OMI Assistant Director Molly Manley, have come up with a plan of action.

They are going out into the community to teach community leaders, healthcare associates, nonprofit workers, educators and more about Healing Centered Restorative Engagement. To help with training needs and to track the impact of their work, U-M’s Poverty Solutions awarded a 2019 grant to them.

“We believe that the trauma-informed care theory holds water, but to work with all of the organizations and schools who have approached us to come in and educate their staff, we needed funding. But in order to get the funding, we needed to analyze existing data to demonstrate that trauma and adverse childhood experiences are a disconnecting force,” Hall says. “We have been doing this work for nearly two years and have seen very positive outcomes. We are very grateful because the grant gives us access to the evidence we need to continue to move forward in our work.”

And they are working tirelessly to do that.

They are featured speakers at this month’s Coalition of Urban and Metropolitan Universities, the longest-running and largest organization committed to serving and connecting the world’s urban and metropolitan universities and their partners; they also presented at the University of Michigan School of Social Work’s annual Fedele F. and Iris M. Fauri Memorial Conference on Oct. 11.

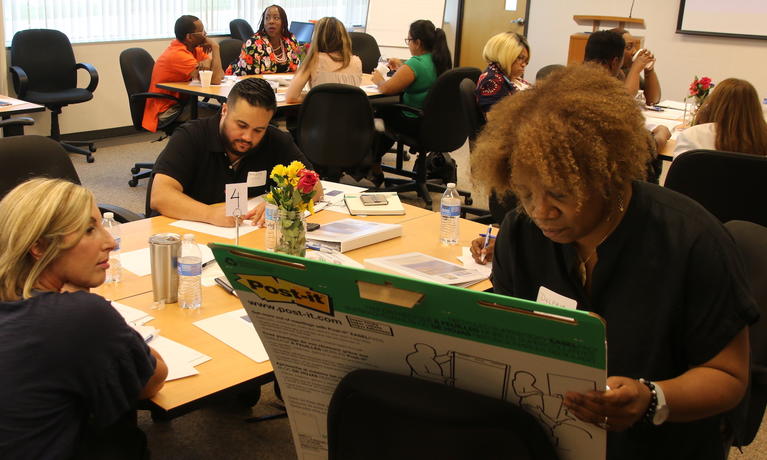

They also provided the first of several trainings to Greater Detroit’s Centers for Working Families Network, a United Way of Southeastern Michigan organized event where Camp spoke to a group of nearly 100 workforce development practitioners and public servants who focus on supporting low- to moderate-income individuals and families achieve goals and greater economic prosperity.

United Way of Southeastern Michigan’s Economic Mobility Initiatives Director Megan Thibos says many of United Way’s Centers for Working Families partners work with clients who have grown up in impoverished neighborhoods and have experienced multiple forms of trauma.

Aware of Trauma-Informed Care and Restorative Practices, Thibos reached out to U-M’s School of Social Work to find an authority in the field. They recommended Camp and her team.

“The team provided a training that was grounded in the latest clinical research but adapted to the unique needs of a non-clinical workforce development and financial empowerment setting,” Thibos says. “Being cognizant of the impacts of trauma can make it easier to connect with others and to truly meet people where they are — in any circumstance, for any purpose.”

Camp, Hall and Manley are pleased with the amount of interest in their work. And more importantly, they are hopeful for the effect it may have in trauma recovery.

“Trauma can be healed at any point in the life course by improving safety and belonging, developing social connections, and creating supportive, inclusive, systems,” Camp says. “By building on that and building on the strengths and resiliencies that people naturally have, we can help people re-engage with life, opportunity and challenge the negative impact of trauma exposure on well-being.”