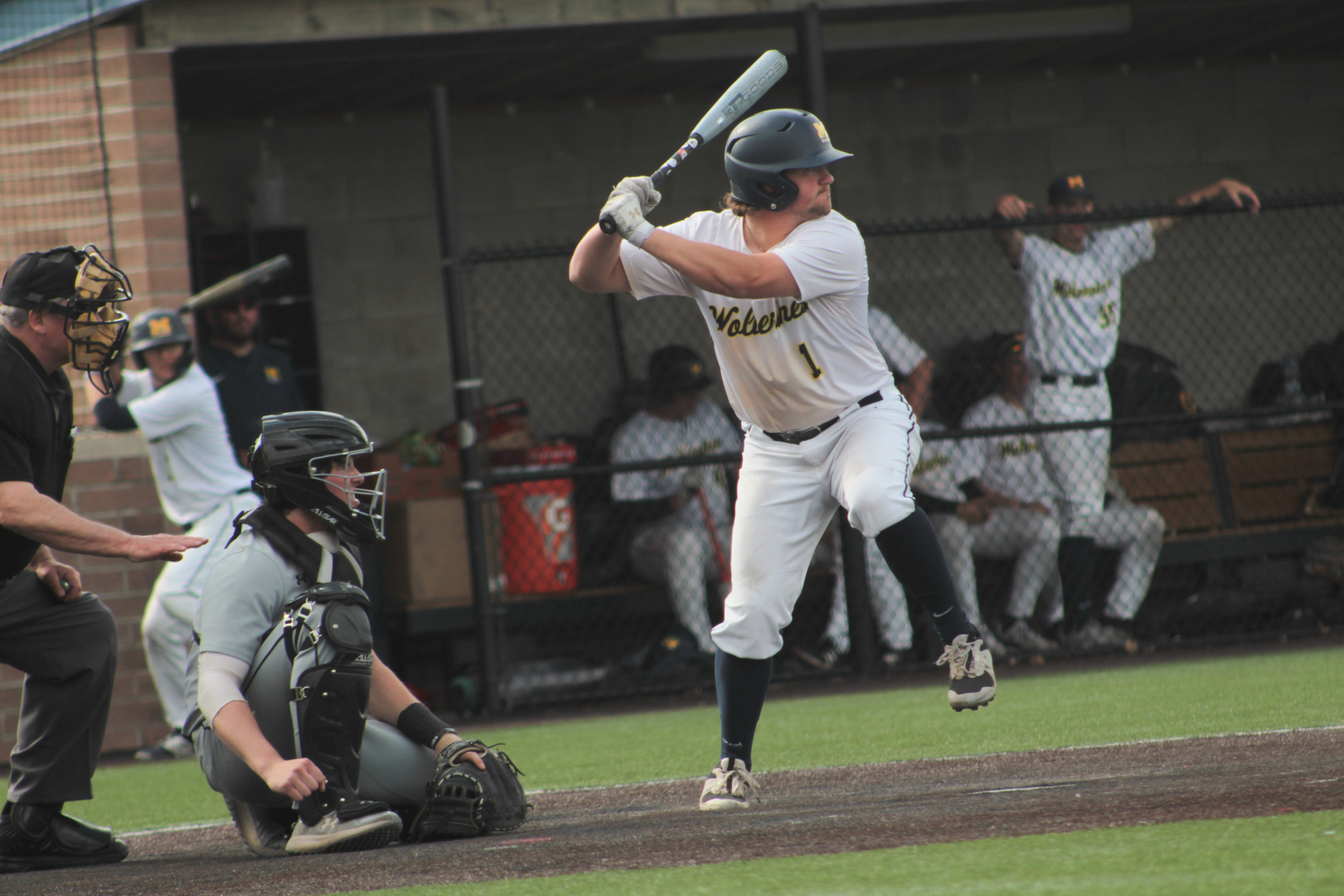

Matthew Williams doesn’t remember a time when he didn’t picture himself in baseball. When he was a 4-year-old kid, the dream was playing in the big leagues. As he got older and more realistic, he imagined being a coach or a strength and conditioning trainer might be where he’d land. His associate degree in exercise science from Grand Rapids Community College put him in a good position for that. But after graduation, he decided to keep going with his education and transferred into the business program at UM-Dearborn, where he also scored a starting position as an outfielder and pitcher on the baseball team. “My thinking was maybe I’d open my own training facility, and I knew the baseball side of things. But I didn’t know anything about running a business,” Williams says. About a semester in, however, he figured out the business curriculum wasn’t for him. Baseball remained the dream, but he’d have to find another path.

Williams took a straightforward approach to finding a new major: He did a thorough survey of the university’s online program catalog and tried to find something that matched his interests and exercise science background. He’d never thought about engineering, but among the course offerings in the mechanical engineering program he found several biomechanics classes. He decided to place his bets there, and it turned out to be a much better fit. He found Associate Professor Amanda Esquivel’s courses particularly interesting, and when he discovered she ran a bioengineering lab that focused on athletics and injury prevention, he reached out to see if she had any open positions. “It was kind of a chance thing,” Williams says. “I didn’t really know that doing research with a professor was something you could do, but a friend of mine was telling me about their experience, so I just sent Professor Esquivel an email and hoped she’d have something available.” It turned out Esquivel did, and Williams landed a position as an undergraduate research assistant. For someone who loved sports and exercise science, it was pretty much a perfect part-time job. In the lab, Williams got to work on several projects that used wearable sensors and video motion capture to research how various movements strain the body, with a goal of preventing ACL injuries. Though many of the studies focused on girls’ soccer, Esquivel also helped Williams with his own independent study, where he analyzed open source data collected on baseball pitchers.

Williams wasn’t necessarily thinking about it when he started in Esquivel’s lab, but the work was basically setting him up for that career in professional baseball he’d been searching for. Elbow injuries, long a problem for pitchers, have become a full-blown plague in the modern game. Today’s pitching is all about velocity, and as athletes try to throw harder and harder, they’re almost literally ripping their elbows apart. Even young pitchers are having to resort to Tommy John surgery — the sport’s now-routine remedy for ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction, named after a former MLB pitcher. Fear of catastrophic elbow injuries is also why starting pitchers going deeper than five innings is now the exception not the rule, something many fans and critics have pointed out has fundamentally changed the nature of the game. Williams says teams now closely track pitching speed and total innings pitched in an effort to ensure their star players don’t end up on the disabled list — or out of baseball altogether.

In the past few years, teams have also started using biomechanics labs to reduce injuries and evaluate prospects. Using the same technology that Williams used in Esquivel’s lab, trainers try to figure out if aspects of a pitcher’s throwing motion are putting them at risk for injury, as well as whether changes to their pitching mechanics could help prevent injury. With high-speed cameras, force plates in the pitching mound and wearable sensors affixed to an athlete’s legs, torso, pelvis, shoulders and elbows, Williams says engineers can actually track how energy flows through the body at critical stages of the pitching motion. The data reveal, for example, if a risky amount of torque is being placed on the throwing elbow. You can also measure whether a change in motion, like a slightly earlier rotation of the pelvis, can reduce strain on the elbow without sacrificing velocity.

As a baseball player, Williams knew that biomechanics labs like this were becoming a big thing in the sport. So as graduation approached, he started looking into whether he could parlay his UM-Dearborn experience into a job. “I basically Googled ‘MLB and biomechanics’ and found a job posting with the Kansas City Royals to work with their pitching prospects in Arizona,” Williams says. Not surprisingly, with Williams’ history as a pitcher, lifelong baseball player and someone who had experience working in the same kind of biomechanics lab, the Royals snatched him up. Williams says it’s basically a dream job — aside from the fact that it’s with one of the Tigers’ division rivals and it’s not actually playing baseball. However, he’s not ready to accept that his playing days are behind him. He points out that he still has one year of college eligibility. And if he decides to go to grad school at some point, he’ll likely take a look at his chances of making the school’s baseball team when deciding where to apply — even if that means being the oldest guy on the field. That, or he says he’s considering trying out for the independent league team near the city he’ll be living in in Arizona — though there’s no chance he’d give up his job with the Royals even if he made the roster. “The pay is like $200 for three months. So, yeah, probably not worth it,” he says. His years at UM-Dearborn, however, seem like they were.

###

Story by Lou Blouin