This article was originally published on December 9, 2022.

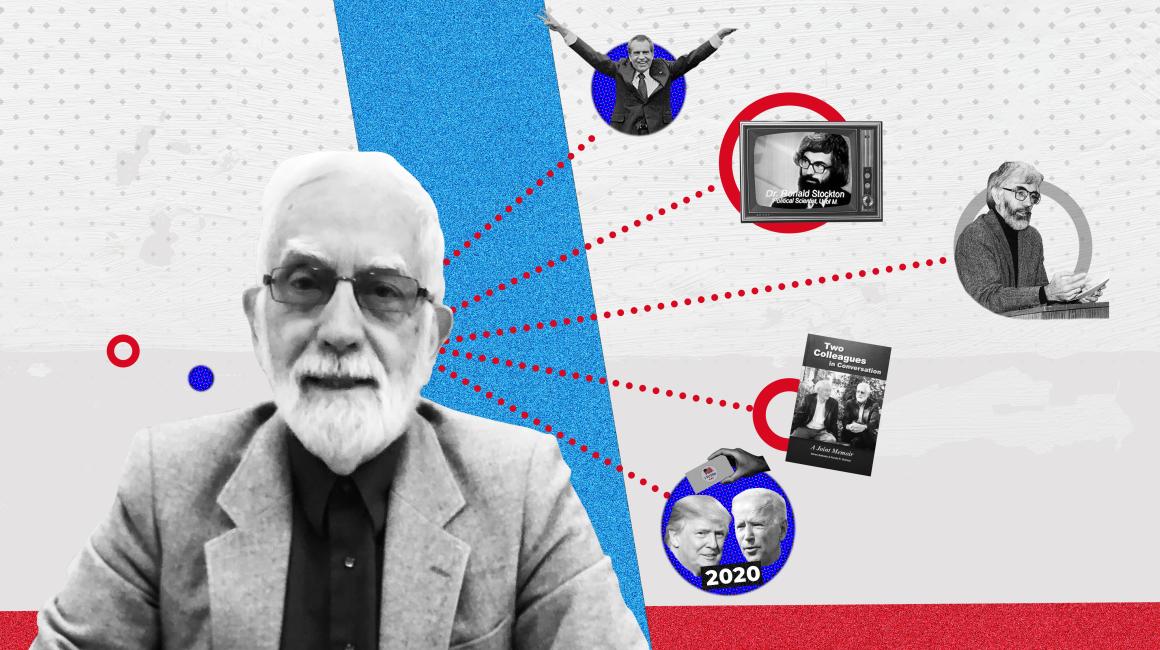

A highlight in Political Science Professor Ron Stockton’s nearly 50 years at UM-Dearborn? The 2020 election.

This is from a man who’s met political leaders from around the world, published several books, and worked with colleagues he considers family — many of whom are now regarded as UM-Dearborn foundational faculty members. “We were a small campus. Our kids played together. It was exciting to help build an institution with people who were deeply caring and intellectually invigorating.”

With so many memorable moments — like watching Professor Helen Graves unapologetically fix President Gerald Ford’s crooked tie before Ford spoke to a UM-Dearborn political science class — what makes the 2020 election stand out? For Stockton, it’s seeing a renewed enthusiasm in the political process among his students. They volunteered to work at polling locations. They participated in political campaigns. And on Nov. 3, they went out to vote.

“Young people are charged up and I’m glad that I was here to see it. About 47 percent of people under 30 voted. Young people often don’t vote and that percentage is a significant increase,” he says. “I’ve been on campus for 47 years — not that I’m counting — and wondered when the right time to step down and retire would be. This is it. The political division in our country is concerning, but I’m optimistic because of the enthusiasm and engagement we are seeing.”

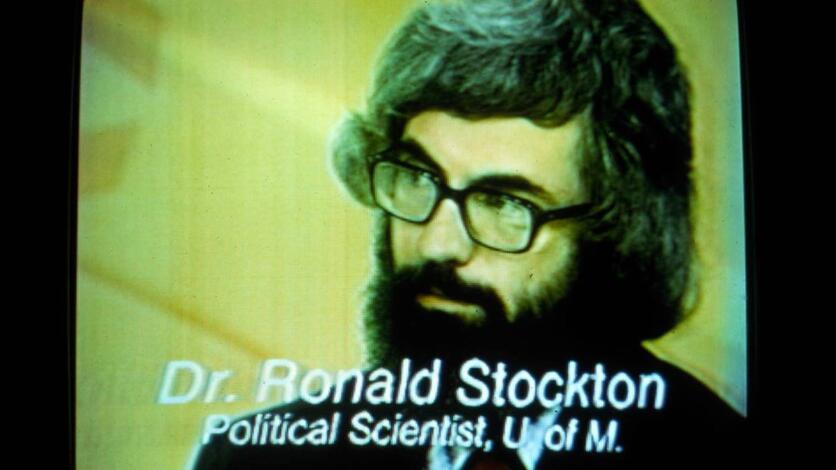

Stockton has experienced decades of political shifts and attitudes since he began teaching on campus in 1973 — a time when news headlines focused on the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal. He says some students were vocal about political issues at the time, but many disillusioned with the government became apathetic toward the political process.

“The government distrust during the 1970s really poisoned young people. In those days, when people got discouraged, they tuned out politics.”

Even when others were apathetic, Stockton stayed vigilant. Noticing how some presidential candidates in the 1970s used divisive statements on social issues like racism, abortion, law and order and welfare benefits to mobilize support, Stockton did his first major research project at UM-Dearborn. Stockton and colleague Political Science Professor Frank Wayman analyzed data they collected through three years of public opinion panels to see if those social issues were divisive enough to create major political party fractures in the future.

“The answer was yes,” Stockton says. “Assuming a two-party system, social issues were going to cause fractures in the parties. We also predicted trends. For example, our study predicted that these social tensions would lead to the election of powerful personalities. We spotted these things before anyone else — and then we watched it happen.” The project and its findings were published as a book, A Time of Turmoil: Values and Voting in the 1970s.

Stockton sees similarities in the political climate from when he started on campus in the 1970s and now. But there are also major differences, which he credits to current political engagement. “Overall people have been disappointed with the 2020 campaign cycle and election. They have voiced feelings of distrust. But instead of apathy, people are meeting the challenges they see with activism and advocacy.”

This is encouraging to Stockton, who looks for ways to pique student interest in politics and create engagement opportunities.

Stockton, who taught in Kenya prior to his UM-Dearborn appointment, developed and taught a course in the mid-1970s on African politics. That course was popular and led the way for additional classes about comparative politics of non-western countries, including Stockton’s now signature PSC 385: Israeli-Palestinian Conflict course. Stockton, who’s traveled to both Palestine and Israel, says he collaboratively created PSC 385 after seeing people react with anger toward UM-Dearborn Lebanese students who denounced Israel following the 1978 South Lebanon Conflict.

“It’s important for our students to have a place to share what is being said in their neighborhoods so we can discuss these things openly and respectfully. Listening to others and learning how to present a point of view in a way that is not trampling on values, dismissive or disrespectful is essential to gaining a deeper understanding,” he says. “We needed a course that explained the history and political structure of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. It’s not about deciding who is right or wrong. Instead, it’s studying the conflict from many dimensions to develop a full understanding of issues and perspectives.”

Stockton says he’s seen students once at odds with each other find common ground. “Unfortunately, political powers involved haven’t learned how to do that. They could learn something from our students.” The class is still a favorite after 40 years — even with retirement approaching, Stockton continues to update the course material to include recent news.

That’s not surprising for people who know him. Stockton is always at 100 percent. This year he advised the campus’ Model Arab League delegations to nearly 20 consecutive years of awards, recorded a public lecture on religious diversity of graveyards in Southeast Michigan, learned how to teach via Zoom, served on the Faculty Senate, published research, and taught a full load of courses.

“It’s important to be active to the end. My students are here to learn and the time we have together is short. So I need to give my all. I turn 80 this month and I don’t want to end up being the guy that students remember for slobbering on his lecture notes,” Stockton says with a laugh.

Fall 2020 is Stockton’s last teaching semester before his 2021 retirement. With finals week approaching, Stockton says it’s bittersweet. He thinks about the students he won’t get to meet. However, before he second guesses retirement, he remembers the decades of students he’s gotten to know and the hope they give him for what comes next.

“My job is to empower students, let them know that they don’t need to be a senator to make a difference, and share my insights into the nature of the problems they see. Then I let them loose. When each class finishes, I think, ‘it’s time to turn this country over to you,’” Stockton says. “Do better than my generation did. Keep that enthusiasm. And I want you to know that it’s been a pleasure being your teacher.”