When someone says, “Be a man,” what does that mean?

To many, it denotes responsibility. To others, it’s keeping conversation topics to sports, politics or work. And, for some, it’s suppressing feminine traits.

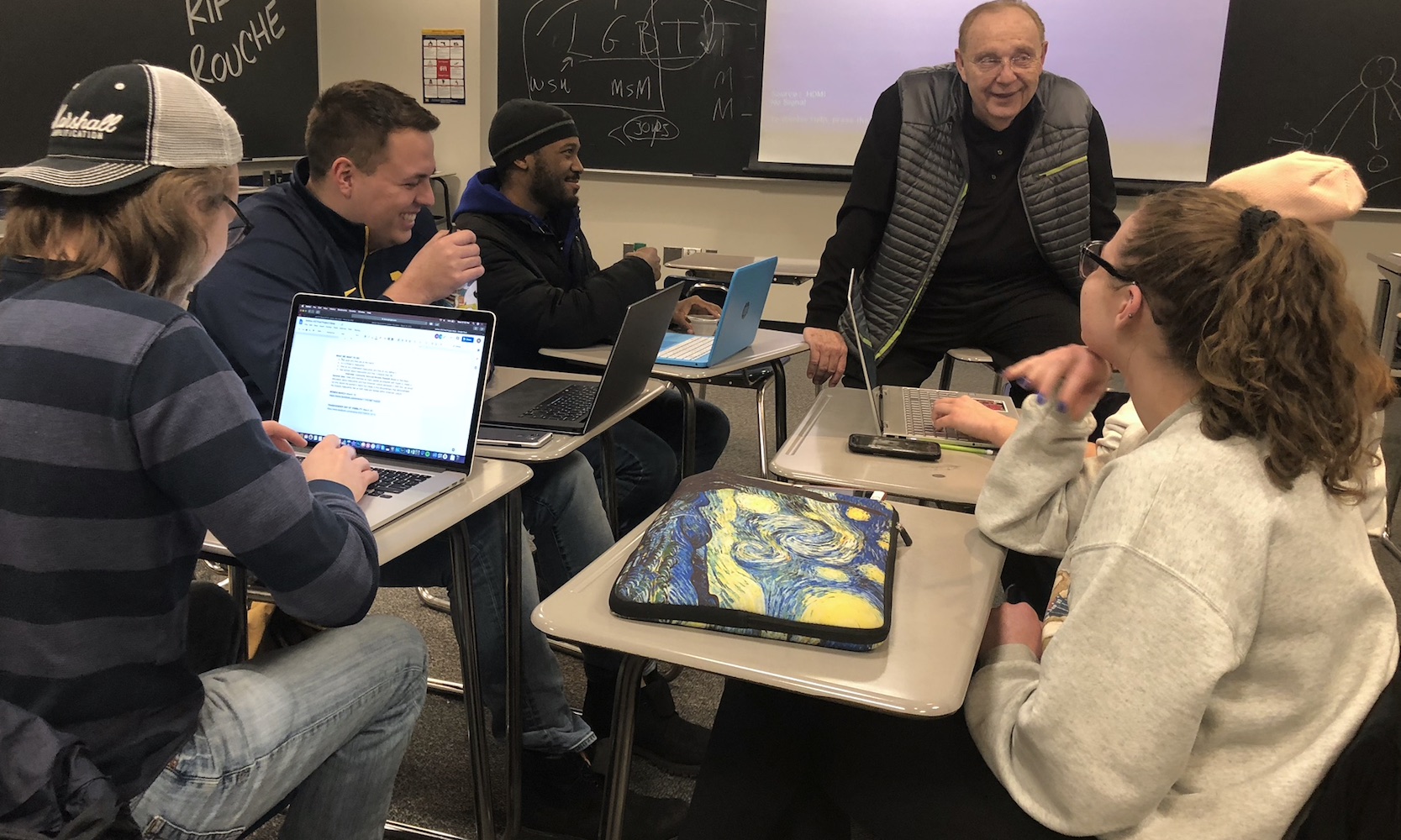

It’s a complicated question that a College of Arts, Sciences, and Letters course explores with nearly 40 students — an equal mix of males and females from a variety of cultures — each week.

Anthropology Lecturer Rick Robinson recognizes that with the #MeToo movement, gender fluidity and toxic masculinity trending in the news, his Men and Masculinities course might seem topical. But the shared sociology, anthropology and women's and gender studies-affiliated course is a campus mainstay that Robinson has taught for nearly a decade. The course was created by Sociology Professor Emeritus James Gruber, a leading national expert on the subject.

Robinson said it is important to acknowledge that males in Western society do have privilege — especially financially stable white heterosexual males — but it’s also important to not dismiss concerns because they belong to people in a majority group. So his classroom offers something many places in today’s society don’t: A safe place and platform to express and learn how difficult it can be to be the right amount of “man enough.”

“Without a clear path to manhood — some markers people have used are puberty, legality (age 18), graduation, military service, an act of violence, financial stability, marriage, virginity loss or fatherhood — we don’t know what makes us men. There is social pressure to be a man. But how do we become one? And where did this idea of anti-feminine come from?” Robinson said.

“We learn, sometimes subconsciously, that to be a man we need to reject what is not masculine. These needs are addressed through group discussion. It’s important to realize that it’s not just about being a good man, it’s about being a good human. And, for that, we need a healthy balance.”

Robinson works to address masculinity from a variety of viewpoints by incorporating text, TED Talks, documentaries and guest speakers into his lessons to show the social and cultural factors that underlie and shape conceptions of manhood and masculinity, particularly in America.

Through personal experiences, reflection and the exploration of other cultures, contemporary and indigenous, the class examines how masculine identities — many with good intentions, but at times misguided — might have developed.

“Since there isn’t a true standard of reaching manhood, there’s a need to constantly prove that we are men and look for validation among our male peers,” Robinson said. “It’s very complex, so I want students to start sorting through what it means to be a man here.”

Nathan Rodwell, a sophomore majoring in data science, said he brings the discussion to the Michigan Marching Band, where he plays drums. Rodwell said the band has optional inclusion-focused meetings where he talks openly about what he learns.

“Regardless of our gender or sexual identity, we all want to be happy. To do that, we need to better understand each other and understand ourselves,” he said.

Rodwell said he’s planning to minor in anthropology — he said data scientists interpret findings from information anthropologists collect — because he wants to learn more about people and culture. He initially signed up for the class for additional credits to go toward the minor and because he had Robinson in a previous course and liked his teaching style.

“I told my girlfriend that this class is something I look forward to every week. But, if I’m honest, I was a bit nervous about enrolling in it; I didn’t know if it was going to be a chance for others to complain about what men are doing wrong,” he said.

“We do talk about difficult things — race, culture, sexuality, politics — but it is all related to the textbook and used as a discussion point to explore it and how we, as men in a society, got here. But no one has been disparaging to me; I’d say the opposite has happened. Women in the class have said, ‘Now I understand why you think this way.’ So it helps us all get to a shared point to work from.”

To get students to open up about their experiences, Robinson has a technique: He asks the class a question multiple times, but frames it differently each time to get different perspectives. He recently asked students about who runs their household — for example, mom or dad — he then asked both the males and females how the structure affects them.

Sharing his experience, one young man raised his hand that his father runs the household. He said that he is interested in theater, but is restricted from studying it or participating in plays.

“I know I’d be good at theatrical performance. But my father associates it with being un-masculine and therefore it would be shameful to have a son in theater. So I cannot pursue this dream. My younger sister is also interested in theater and my father allows her to participate, but she’s restricted in other ways,” said the anonymous student. “I don’t understand why it is shameful to pursue your interests.”

Robinson said it is important, using an example like this, to challenge the socially passed down perceptions of gender norms and personally re-evaluate them. If these constructs are causing confusion, repression or anger — which Robinson has seen and experienced — exploration of what masculinity means on a personal and societal level is beneficial not just for people today, but for future generations too.

“Masculinity is not as narrow as it is sometimes presented to us. We, all genders, need to be open to rethinking what masculinity is and what men should be doing. Men cannot be all things to everyone — be strong, but not too strong; lead, but follow; don’t cry, but be sensitive,” Robinson said. “This class is to empower men to take in the messages they are getting, understand them, and examine who they are as a person and how they want to move forward.”