This article was originally published on November 10, 2021.

Michigan has been facing some version of a teacher shortage for about a decade and a half, but for faculty in UM-Dearborn’s education department, the current moment still stands out. Associate Professor Danielle DeFauw says she’s getting emails “all the time” now from principals, superintendents and teachers “begging” for graduates or soon-to-bes who might be looking for a job — even though usually “95 percent of them” have already been hired somewhere. CEHHS Associate Dean and Professor of Educational Technology Stein Brunvand says he’s aware of a rural district that was offering unheard of $10,000 signing bonuses for three-year commitments for new hires — and other schools that were filling vacancies with teachers working remotely in other states. For Interim Chair and Associate Professor Chris Burke, the shortage has gotten personal. “My daughter’s school has actually shut down for the day — and I’ve heard of this in other districts too — simply because they don’t have enough staff,” Burke says.

The scarcity of teachers has also exacerbated another well-documented trend: teacher poaching. “School districts are now in a pretty fierce competition with each other, and districts that can offer higher rates of pay often poach teachers away from lower-paying districts,” says Assistant Dean for Assessment and Accreditation and Professor Susan Everett. “So, for example, a brand new teacher might get a job and then a wealthier district might hire them in a year or two after they have some initial experience. We are hearing this is a growing problem for some of our partner schools. So the challenge is not just getting teachers, it’s keeping them.”

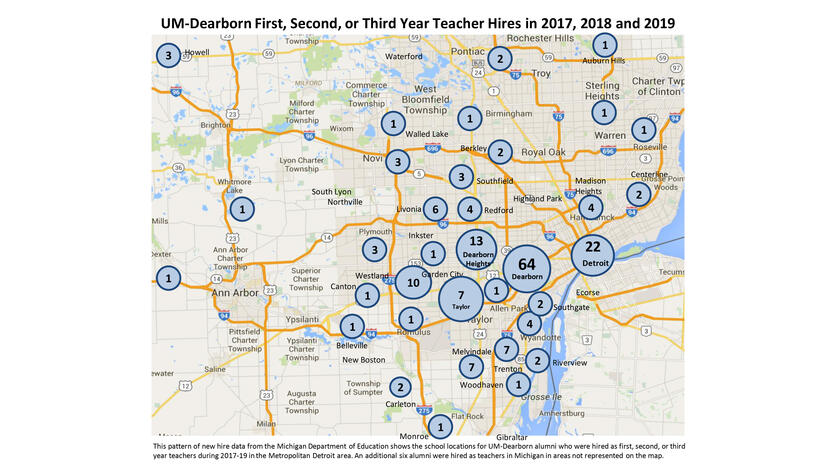

Against the backdrop of this market dynamic, in which teachers, even new ones, often have their pick of positions, faculty have noticed an interesting trend: Many of our graduates are actually flocking to districts where it’s traditionally been challenging to recruit. Look at UM-Dearborn’s first, second and third-year teacher hires for 2017-2019 and you’ll see that nearly half of graduates have taken positions in Dearborn or Detroit — two areas where the need for teachers is particularly acute.

So why are so many UM-Dearborn graduates filling vacancies and serving students in areas most impacted by shortages? Burke, Everett, DeFauw and Brunvand say it’s important to remember that each teacher’s reasons for choosing a school are complex and personal, but they have some ideas about what may be fueling this trend. DeFauw and Brunvand say demographics may be an important factor. Brunvand says the commuter nature of our campus means that many of our students remain rooted in the communities they grew up in throughout their college years. That deepens their young adult ties to an area — some even have or start families as students — which makes staying more attractive and moving more disruptive to their lives. DeFauw says some students, especially Arab American students from Dearborn and Detroit, also express strong feelings about staying in their communities where they can use their bilingualism and continue to build what’s arguably the most vibrant Middle Eastern community in the U.S. They say there’s often a similar sentiment among students who grew up in Detroit, who feel a sense of belonging there and a desire to serve students with similar backgrounds to their own.

Such factors likely don’t serve as a total explanation, however, given that faculty observe that many students who choose high-need districts don't have personal connections there. Here, the ethos of the department’s student teacher placement strategy may be shaping teacher choices. It’s true that accreditation for education programs requires that students experience a diverse range of school placements during their teacher preparation programs. But UM-Dearborn faculty have been deliberate about cultivating core partnerships with high-need, socioeconomically challenged districts. For example, years ago, impressed by the work of a teacher who built an outdoor classroom, Burke fostered a partnership with Neinas Dual Language Learning Academy in Southwest Detroit. “I wanted my students to see that there were strong assets in this community — that there were great teachers, and excited students, and parents who were committed to their children’s education — because that’s not the narrative that my students had about public schools in Detroit. Initially, when you ask students what they know about the city, a lot of them will tell you about the lack of resources and the poor quality of education. To be able to go in and show them something different disrupts that whole way of thinking. Yeah, it’s complex. There is poverty and there are struggles. But there is also ingenuity, and entrepreneurship, and hard work, and joy that are part of this community.”

Burke notes that such experiences often require “mediation” from faculty to be most effective. Just placing preservice and student teachers in a school, without giving them context often doesn’t lead to the best result; you have to deliberately guide students to see a school or a community from an asset point of view, which can also serve as an antidote to the “savior complex” that often afflicts new teachers who come from the outside. Other times, DeFauw says you simply have to be a little tough. There are times when students push back about their placements, and she has a variety of ways to calm their nerves. “As a first step, I ask them to simply take a drive there, on a Saturday or Sunday, when no one’s at school and just check it out,” DeFauw says. “Often, I find they’re just nervous about the drive or have ideas about a community that can quickly get erased if they actually go there.” If she needs to deploy an extra nudge, she can lean on department policy. Some universities offer their students a two-week tryout period for placements, and the insurance of having an out is usually enough to get a nervous student into the classroom, where most find their stride. “We don’t give our students that out,” DeFauw says. “We think that can be disruptive to our partner schools and the students they’re teaching. And we want our students to have new experiences, even — maybe especially — ones that make them feel a little uncomfortable. I tell them that’s just going to make you a better teacher for your future students. I still think if you go into a school, and you see kids who need to be taught, if you’re a teacher at heart, you’re going to feel a part of that.”

College of Education, Health, and Human Services Dean Ann Lampkin-Williams thinks there might be one more factor why our teachers are making an outsized impact in districts with the strongest need: A compassionate roster of faculty who are cultivating a culture of respect in choosing that path. “What I hear from our students is that our faculty allow them to be themselves,” Lampkin-Williams says. “They can be honest with someone like Danielle and say ‘I want to teach in this district’ and they don’t have to be ashamed about it. It’s not less-than to want to go back to your high school in Dearborn or your elementary school in Detroit. I don’t think we’d see this happening without our faculty validating these choices. They aren’t attempting to choose what’s best for our students. They’re allowing students to see the value of having pride in what matters to them.”

###

Story by Lou Blouin. If you're a member of the media and would like to talk with someone from the UM-Dearborn Department of Education about this topic, please drop us a line at [email protected] and we'll put you in touch.