It was beginning to develop a reputation as the unfinishable project. In fact, UM-Ann Arbor Emerging Technologies Librarian Patricia Anderson spent nearly a decade trying to fulfill her vision of a video game that could help kids better detect online predators.

A few years ago, the ambitious goal even stumped one of Computer and Information Science Professor Bruce Maxim’s senior design teams, whose attempt fizzled when they got stuck on the game art. Understandably, when Maxim said he’d found another group of seniors willing to take a run at the project this year, Anderson said she kept her hopes in check. Best case scenario, she thought she’d end up with a good enough start to launch a Kickstarter campaign.

But after eight months of steady work, the team, anchored by Sean Croskey, Luke Pacheco, Aristotelis Papaioannou and Dominic Retli, has blown through those expectations.

Today, they’ve got a fully functioning, retro-inspired, Nintendo-esque, video game (a style that just so happens to be having a bit of a revival moment right now). Even more impressive, the middle schoolers they tested it with dug in just like it was any other video game.

“When I heard the kids freaking out when they got to the bear chase, it was like, ‘Yes—we did it,’” Papaioannou said, smiling.

The roots of the project are personal for Anderson. She’s a longtime advocate for people with disabilities, who, she explained, often face greater risks online.

“Any of us can be targets,” said Anderson, who works in the Taubman Health Sciences Library. “But it’s not at all uncommon for people with a range of physical or intellectual disabilities—or even those who are homebound—to rely on the online world for a lot of their social interaction. That can be really empowering, but also risky. And we wanted to help people who are navigating in that world understand how to protect themselves, and not share too much personal information with others they don’t know.”

A video game, Anderson thought, could be a solid training ground to build those skills.

To develop the game concept, she enlisted the help of her son, who has autism, and together they worked out a story anchored by a classic video game quest. During the course of your adventures, you’d encounter a variety of characters—some good, some who just pretend to be good.

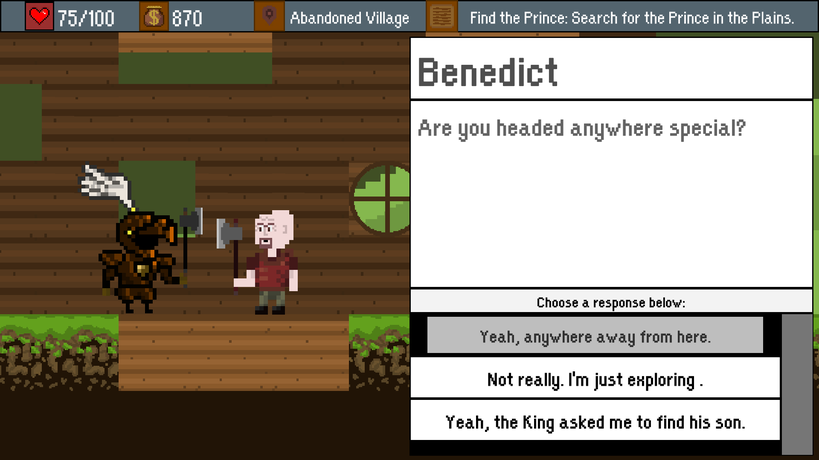

In the game Ab Errantry, you play the role of a knight helping find a princess or prince (your choice) who has gone missing. Along the way, you meet characters who can help your mission by providing vital information; and others, who appear helpful, but are really out to harm you. To figure out which is which, you engage in dialogues with the characters and make decisions. The different scenarios are meant to be an analogue for the kinds of situations that could get you into trouble online.

“For example, one character is a lady who tells you she’s lost her Siamese cat,” Pacheco said. “She’ll ask you to go through this door to help her look, but if you ask her more questions, you realize her story doesn’t quite add up.” If, on the other hand, you just trust her and walk through the door, there’s a goblin waiting on the other side.

The team carefully scripted these parts of the game, working with Adam Grandt, a information security consultant who analyzed linguistic patterns from actual chat transcripts involving online predators. But they also wanted the dialogues to feel natural.

“We had to make sure it didn’t sound too preachy,” Croskey said. “For the game to be effective, the kids have to interact with the characters as they would in real life. If they got a sense that we wanted them to answer in a certain way, they might do things just because they knew it could help them beat the game.”

One of the clever parts of Ab Errantry is players don’t even know it’s a teaching tool until the very end. That’s when a post-game wrap-up helps you analyze the decisions you made, giving you constructive criticism about what you could have done better. Until then, it pretty much just feels like you’re playing a cousin of the original Mario Bros.

And though this initial version was built as a tool for kids with autism, the dialogues are all customizable. In fact, the whole game is completely open source, creating an opportunity for multiple applications. Anderson said others who’ve looked at it see potential for using the game with kids with other learning or physical disabilities, those who have been bullied and retreat into an online social world, or even with seniors vulnerable to online scams.

The game is not only a realization of a long-held dream for Anderson, but a major accomplishment for the students who built it.

At the recent CECS senior design competition, the project took home the Computer and Information Science Department’s first place prize and tied for most innovative.

When asked about their success, the team members earnestly credit “every year and every class” of their education—which they said gave them the huge array of skills you need to do something as audacious as building a video game from scratch.

“It kind of felt like it took four or five years of experience and mashed it all into one project,” Papaioannou said.

“And I think we succeeded because we didn’t underestimate it,” Croskey added. “People think you just start with a game engine, you put in the art, and everything else is done for you. But really, almost everything in there—from what happens when a character falls to all the database work behind the scenes—we did ourselves.”

He’s not exaggerating. Team member Dominic Retli even wrote the original music for the game; and he and Papaioannou hand drew many of the characters to supplement the game artwork donated by Chicago-based artist Alex Van Trejo. They didn’t get any classroom training for that.

But that’s the kind of pluck it takes to finish the unfinishable.