This article was originally published on November 19, 2019.

‘So you like art, design and psychology? Maybe you should consider studying engineering.’

That’s, of course, not typically how the conversations go with prospective students. More often, it’s an affinity for math and science that’s considered the natural gateway into the field. But the faculty behind a new Human-Centered Design and Engineering (HCDE) master’s program are making the case that students interested in things like the arts, humanities and social sciences can find their place in engineering. Students seem to be getting the message, too. A little more than a year after launching, enrollment in the HCDE program has boomed. And the program’s director, Associate Professor Sang-Hwan Kim, says he’s now fielding emails almost every day from prospective students.

Most often, Kim says, they’re interested in two things. First, the career opportunities, which are plentiful and varied (keep reading for more on that). And second, whether it’s really true the coursework for this engineering degree doesn’t include a single advanced statistics or mathematics class, but plenty in art, design, psychology, anthropology and marketing. That’s indeed the case. And it’s a fact that demonstrates perhaps better than any other just how different human-centered design (HCD) really is — and maybe why more companies are trying to harness its power.

While HCD encompasses a lot of diversity, its central concept is that the design process is best served when you start with a deep understanding of your audience. ‘Deep’ is the important word here. So way before building a prototype — and even before getting too far into concept development — human-centered design engineers deploy all kinds of methods to get to know what their potential human users really want and need. That could include things like extensive interviews, having users mock-up impromptu “low-fi” prototypes of new devices, observing people in relevant real-world environments, or in some cases, doing full-blown ethnographic studies. Given the emphasis on understanding how people think and live, it’s easy to see why classes in human factors, anthropology and psychology are a key part of the HCDE course work.

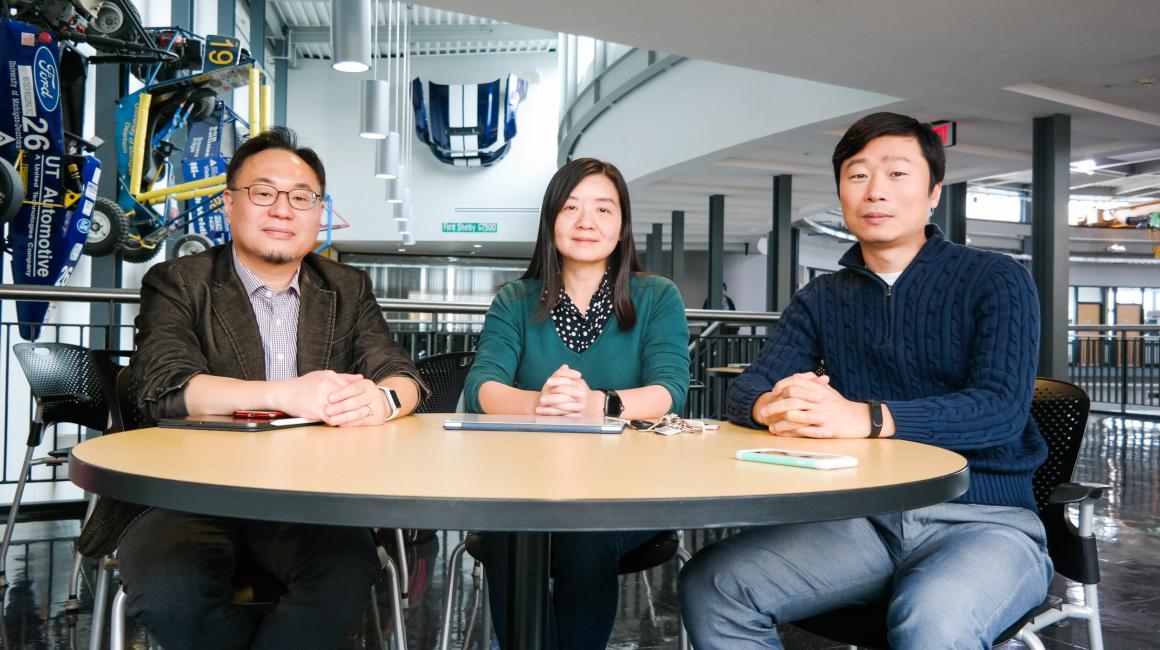

The idea, says Assistant Professor Feng Zhou, is that if you don’t understand your audience, “you might design something that doesn’t solve the user’s real problems and thus has no meaning to them.” That sounds intuitive enough — and perhaps even begs the question about why engineers would do it any other way. But Associate Professor Shan Bao explains that, for a long time, the human user was only a secondary consideration. In fact, Bao says the human factors field, a cousin of ergonomics and a key component of HCD, emerged from a high-stakes problem during the World War II era. In trying to solve a mystery over the high frequency of aircraft crashes, investigators discovered that pilot error, not equipment failure, was most often to blame. Specifically, the pilots, even the highly trained ones, were struggling to interpret the complicated instrumental panels in the cockpit.

It’s an example that reveals just how machine-oriented the engineering philosophy was at the time. Back then, the layout of the airplane cockpit was almost an afterthought, because it was assumed that through the proper training, you could teach a human to operate it — no matter its design. In this way, the human was almost “designed” to fit the machine. It turned out to be an approach with some costly consequences.

HCD flips the emphasis entirely, banking on a deep understanding of the user — even the user’s limitations — to drive the design. It’s a philosophy that’s gradually, over decades, infiltrated more of the engineering process — especially, Kim says, since the smartphone revolution. Today, a huge range of companies and organizations are embracing HCD as a design philosophy. For example, during a recent visit to the UM-Dearborn campus, Ford Motor Company’s Darren Palmer talked about how their aggressive development of new electric vehicles is being powered by human-centered design. But Zhou points out HCD is also helping young engineers move into less commercial realms. In particular, he sees it as an extremely powerful tool for developing assistive or adaptive technologies for people with disabilities; or building technologies for raising living standards across the globe.

‘In designing systems for water access or sanitation in developing countries, we shouldn’t assume the solution is to simply deploy the large, expensive systems we use in the developed world,” Zhou explains. “Instead, you have to start by learning how people live, what their needs really are, and then develop technologies that fit their lives, the geography they live in and the resources that are available.”

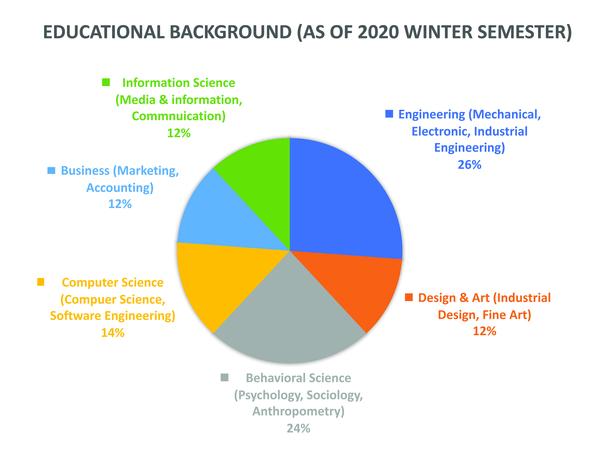

That diversity of application is part of the reason Zhou, Kim and Bao think the new program could attract students who never would have considered engineering before. They’re already seeing some of that. Kim says about half of those now enrolled are currently working in the automotive industry. But about half of all students are coming from backgrounds that include art, design, business and the social sciences.

Master’s candidate Jayne Spence calls herself an “outlier” among her HCDE classmates, who are mostly engineering students. But it might be more descriptive to say she has a foot in both worlds. As an undergraduate, she studied industrial design at the University of Cincinnati, which meant her classmates were mostly fashion, graphic, digital and other industrial designers. Today, however, she’s an Experience Designer at Ford, which means working alongside “20,000 engineers every day.”

“One of the reasons I was drawn to this program is that I thought it might help me develop a more technical background so I could be a better communicator,” Spence says. “And I feel like that’s already beginning to happen. I’m starting to garner more empathy for my engineering colleagues, especially for their rigorous data collection. And I’m able to use more of the vocabulary when I’m trying to communicate my own ideas, which I think helps break down the silos we typically operate in.”

Kim says that’s exactly the mindset they’re trying to nurture in the HCDE program.

“I’ve worked on many teams that were half designers and half engineers, and I see a kind of ‘membrane’ between them,” he explains. “Engineers are good at providing the rationale for why they’ve done something, but may lack creativity. And designers are really creative, but they can’t always explain why something should be the way it is. In my view, these are two different mental models, and they can be in conflict or they can complement each other. I see it as my job to make this membrane more permeable, and to bring our two worlds together.”