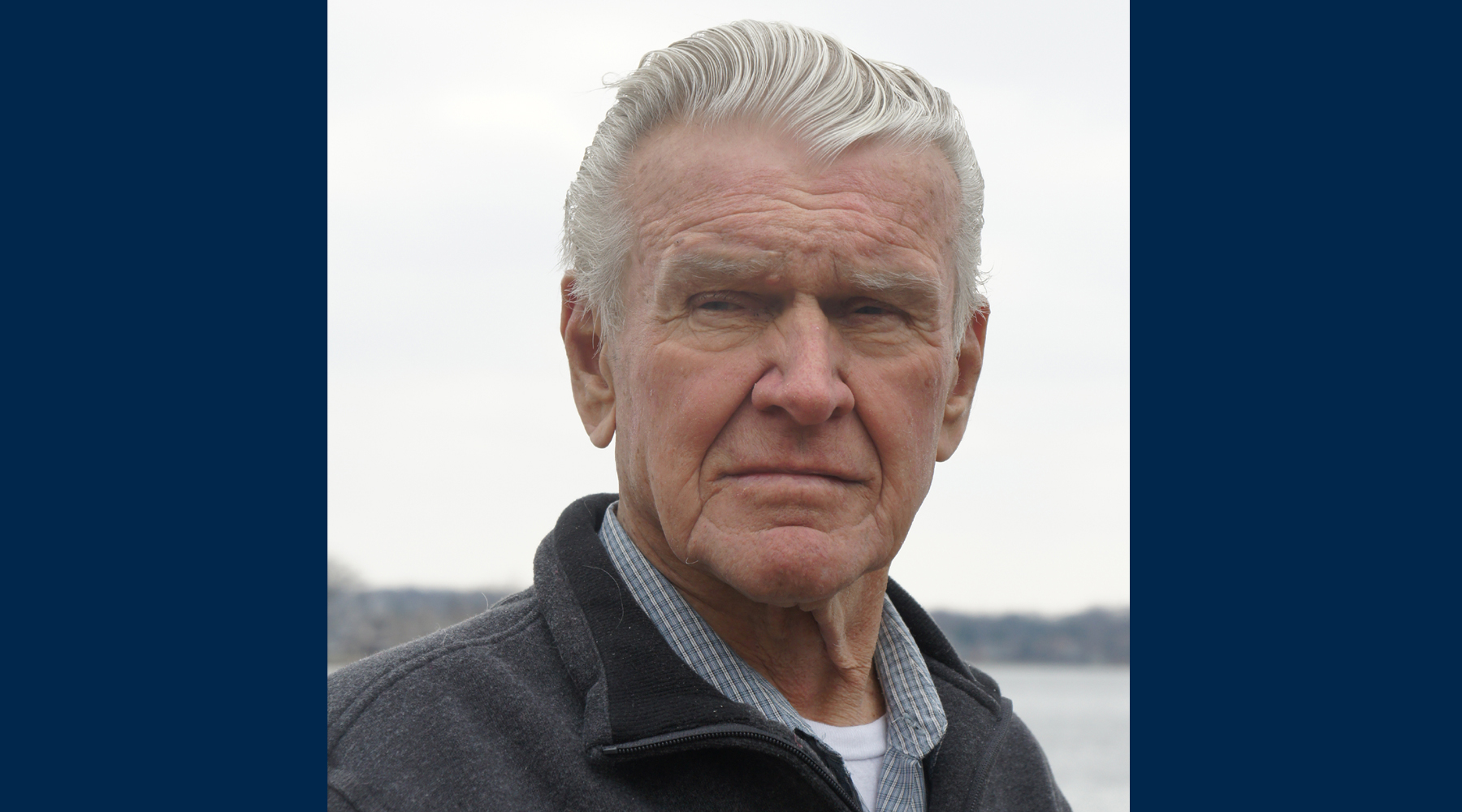

Professor Bob Little, who died in June at age 86, had a career at UM-Dearborn that spanned an incomparable 54 years. That longevity made him a fixture in the mechanical engineering department. But it was his unapologetically tough academic standards, straight-talking personality and penchant for sprinkling his liberal political views into lectures that made him a legendary figure on campus.

“Bob was definitely from a bygone era,” Professor Subrata Sengupta recently told us. “He was one of the most direct and honest people I’ve met. Of course, some people can find bluntness challenging, but I personally enjoyed it very much. These days, people are careful about what they say, but Bob had no problem telling you exactly how he felt about anything.”

Sengupta says that included outspoken views on everything from department policy to politics to industry practices. But such directness allowed the two of them to build an unshakeable trust — particularly when Sengupta was serving as college dean. “Because Bob would never say anything he didn’t absolutely mean, you always knew where he stood. And his values were rock solid. That is a particular kind of personal integrity that is not as easy to find as you might think.”

Little didn’t spare his students his old-school approach. He was known for being uncompromising in his standards and preferred they learn through hard work and making mistakes rather than cutting them breaks. A traditionalist in the classroom, his approach to research was anything but. As a young faculty member in the 1970s, he was a pioneer of statistical and mathematical approaches to design, which focused on incorporating the real-life variations inherent in materials and manufacturing processes into the design process. It was a forward thinking philosophy that’s now standard practice in mechanical engineering.

Professor PK Mallick says his friend and colleague was also known for his compassion and generosity. A husband and father of four, Little supported his kids as they pursued their own higher education dreams, and even put several members of his extended family through college. Despite being opposites in many ways, Mallick says he and Little also collaborated on research multiple times during their overlapping careers.

“I still remember the day he approached me and told me he wanted to work with me,” Mallick says. “It was very unexpected because he was senior faculty and I had only been here a year. But I think he saw that we had some shared interests, and even though I’m sort of easy going and Bob was very colorful, it just worked. I still think of Bob as someone who was very kind to me.”

Both Mallick and Sengupta say among the things they’ll miss most are their chance conversations with Little, during which you could always count on him for a passionate point of view.

“Most of us go through life having sort of pro forma conversations,” Sengupta says. “We know what we’re saying and it doesn’t mean much. But as long as we’re nice to the other person, it works. It’s comfort food, and we need that in life. But let me put it this way: Bob was not comfort food — and I liked that very much.”