Salary, benefits and hours are explicitly agreed upon prior to job acceptance; if there’s a change after hire, there’d be consequences. But what happens if the informal obligations or workplace perceptions developed prior to employment don’t match reality?

Turns out, there are major ramifications for both employee and employer. “Anyone who’s ever worked is saying, ‘Well, of course there is,’” said College of Arts, Sciences, and Letters faculty member Marie Waung. “In this research, we needed to first scientifically test it — and not operate on assumption — to dive into what happens when these perceived obligations are not met. That’s where it gets really interesting.”

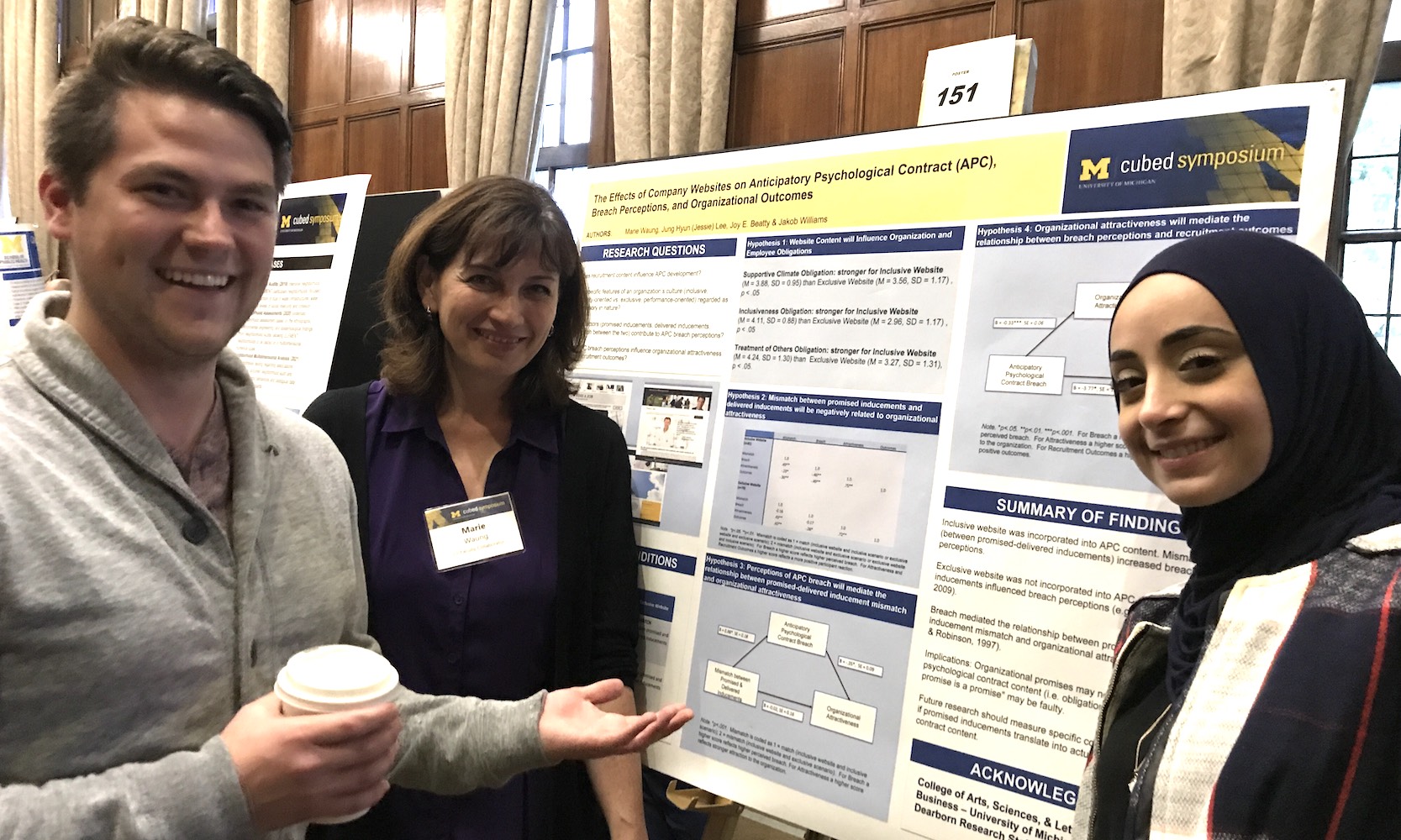

Interdisciplinary research by Waung, along with College of Business faculty Junghyun (Jessie) Lee and Joy Beatty, focuses on employees’ expected obligations in the workplace, known as psychological contracts, which include non-legal binding job elements like office environment and culture.

The research is among the first to examine these psychological contracts in the developing stages of the employer/employee relationship.

“Currently, studies have focused on the psychological contract after employment begins. But the psychological contract begins to develop even before an employee starts a new job. For example, information given during recruitment might affect psychological contract content,” said Waung, psychology professor. “If the ultimate goal is improving employer/employee relationships, then we need to better understand the psychological contract, and one way to do this is to study how it develops.”

Waung argues that psychological contracts begin to form before employees are officially hired, and that if these expectations are breached there can be a negative effect. Examples include a company visually championing inclusive practices on its hiring website, but not having those built into its corporate culture. Or a recruiter giving examples of exciting job experiences, but the reality of the position is menial tasks.

“Ample research has shown that employees are willing to perform extra work tasks, above and beyond their job description, if they feel they are treated fairly and with respect. But why would someone want to go above and beyond if they feel the employer has deceived them by making false promises about the work environment? Most wouldn't," Waung said. “And companies sometimes need you to go beyond because everything can’t be specified in a job description; it would be overwhelming.”

The two-part project was sponsored by MCubed, a University of Michigan research-based initiative that distributes seed funding to trios of faculty that include at least two different campus units. In the first study, they examined the effects of websites and recruitment message content on new employee expectations and on the subsequent development of — and potential violation of — psychological contracts.

“For organizations, the study suggests that it is important to pay attention to what companies communicate on their recruiting website, given its promissory nature, for an effective employee-organization relationship even before formally joining the organization,” said Lee, assistant professor of organizational behavior and human resource management, whose primary research area is in psychological contracts.

The second study surveyed a combined 200 students across all three U-M campuses in a variety of disciplines before and after their internship experience.

“This was so we could gather data from a group of people with fewer established workplace expectations; people at the very beginning of their career. We found that even when people didn't know what to expect, psychological contracts still developed,” Waung said. “When broken, students tended to no longer consider the employer for full-time employment, and — perhaps more of a concern for recruiters — told their friends to avoid that employer. So there were rippling consequences.”

Beatty, associate professor of management, said this MCubed research topic is important for recruiters and relevant for students because the implicit expectations between the employer and employee are so often taken for granted.

“For my organizational behaviors classes, it's helpful to remind students that the expectations they form regarding their employment prior to starting their jobs can influence their satisfaction in the job down the road,” Beatty said. “It's also a good reminder for employers to make sure they deliver the items they promise in their recruiting materials and interviews prior to employment.”