Returning to school in her late 20s, a SOAR Program student now is interviewing for a Fulbright Scholarship. Another student’s examination of a nonprofit’s customer needs landed her a full-time position with the company of her dreams. And, wanting to help low-income students, a junior analyzed data and is now seeking assistive strategies.

That’s the transformative power of research.

On campus, undergraduates are doing a variety of research across all four colleges. And, for many of the projects, these students are a part of the process from concept to found results.

“Undergraduate research is part of the university’s mission because it serves a triple function. It gives back to the community, educates our students by learning through doing, and helps them cultivate a marketable skill,” said Psychology Associate Professor Caleb Siefert, undergraduate research coordinator in the College of Arts, Sciences, and Letters.

A National Science Foundation-funded study found that undergraduate research opportunities increased understanding, confidence and awareness.

Most (88 percent) respondents for the surveys, which began in the mid-2000s, reported that their understanding of how to conduct a research project increased a fair amount or a great deal; 83 percent said their confidence in their research skills increased, and 73 percent said their awareness of what graduate school is like increased.

Siefert said he sees the benefits gained here. And they go beyond the campus too—not just into the community, but into the students’ future.

“Our students come to us with ideas, work with the data, write academic papers, present at conferences and more,” Siefert said. “Whether you are looking to go on to graduate school or find a job in industry after graduation, those skills will transfer. The research they do here gives them a running head start in the race.”

Discovering what’s next

Before a new technology goes into the field, it needs to be tested.

Jessica Buice, a mechanical engineering and bioengineering major, was chosen by Mechanical Engineering Assistant Professor Amanda Esquivel to help with wearable technology research.

Buice is currently working with two wearable activity-tracking projects—a knee-based apparatus that tracks female athlete movement with specific attention to the ACL, a frequently injured ligament for female basketball and soccer players; and a head-based one that tracks head acceleration and impacts in sports like lacrosse and soccer.

Esquivel’s goal is to use wearable technology for injury prevention by tracking movement and impact for athletes.

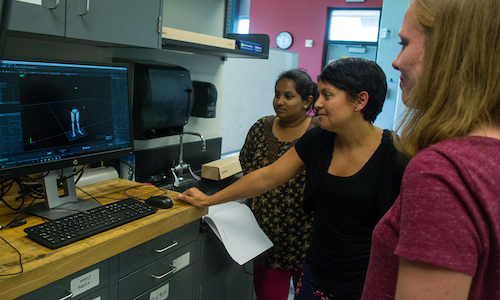

In the BioDynamics Research Lab, Buice places reflectors on the participating human research subject, gathers data from the 12-camera motion tracking systems and analyzes it in a specialized biomechanics software program.

“I’m working with cutting-edge technology that, before this, I only heard about in a class lecture or was able to see in a class demo,” Buice said.

Buice learned of the research opportunity while at a Society of Women Engineers (SWE) networking lunch for female engineering faculty and SWE group members. Esquivel shared information about her research and the lab. She also mentioned she was looking for an assistant.

“As soon as I heard that, I thought, ‘Pick me.’ I didn’t know undergrads could even do research,” said Buice, who has now worked with Esquivel for 18 months. “Since then, I’ve learned how to write an academic paper—which was completely new to me because I’m a numbers, not words, person. I’ve had IRB training and I know what that process is like. I’ve presented at a national conference. I’ve always found engineering to be interesting, but this has proven that it’s right for me.”

Buice said the work she’s done will help her no matter which path she chooses to take.

“This research experience gives me options. I’ve gained skills that could help me if I work for a company, go to a research institution or continue on to graduate school, which I’m now considering,” she said.

With one of Esquivel’s wearable technologies recently validated in the lab—the one tracking head acceleration—it will soon be available for in-the-field testing. And Buice can say she had an important role in getting it there.

“This work has been so interesting to me. We are looking at ways to prevent injuries by advancing knowledge. I feel like I’m helping make a difference.”

Educating the next generation

When Robin Wilson was a young child, she had an interest in learning a second language. Wilson, who was raised in Inkster, Mich., said there weren’t many options for her in school.

“But there was a summer camp down the block from my house where a camp counselor taught us Japanese through song and art. I still remember thinking how I’d like to understand and speak another language,” she said. “It’s interesting how one experience can plant a seed.”

A nontraditional student in her 30s, Wilson—a reading major earning a K-8 teaching certification and a SOAR program student—looked at ways she could make an impact on students in urban environments.

Wilson wanted to research effective culturally responsive foreign language instructional practices. And through Reading and Language Arts Associate Professor Dara Hill, Wilson got her chance.

Wilson was placed in a kindergarten classroom at Detroit’s Foreign Language Immersion and Cultural Studies School, one of the few urban-centered foreign language programs in the country.

There, the classroom teacher merged African-American culture into the learning of French as a second language.

“When the students answered correctly in French, she’d say a relatable colloquialism like, ‘You’re on fire!’ I could see how much the students liked that,” Wilson said.

After her semester-long classroom experience, Wilson shared her research, which was advised by Hill, “Foreign Language Immersion in an Urban Context: A Culturally Responsive Approach to Teaching French to African American Kindergarten Students,” at the 2017 Meeting of Minds. Wilson also has submitted a paper with the same title for publication.

Among Wilson’s findings: The use of music, oral storytelling and culturally responsive texts were effective in the students’ learning of a second language, evidenced by their ability to use French words in the proper context and sharing personal stories in response to readings.

Inspired by her research experience, Wilson decided to fulfill a childhood dream.

She began to take French courses. She did a study abroad experience in Quebec to test her skills. And she just completed a language evaluation for a Fulbright English Teaching Assistantship in Senegal, West Africa, and her interview was entirely in French.

In her future classroom in the U.S., Wilson plans to incorporate various francophone cultures into the class language learning experience.

“I want to share West African cultures with students because French is spoken in many countries in that region,” she said, adding that she wants to show African American children that people who look like them speak French too.

Wilson said she wants to open more doors for those future students—and learning a second language is one way to do that.

“Children—especially those in schools with limited district funding, teacher shortages and other issues—need doors opened for them. The more doors, the more paths to opportunity,” Wilson said. “I wanted to help children, who are growing up in a community like I did, to have access to learning a second language and be excited about it too.”

Improving the community

When Galen Mueller walked into the College of Business’s iLabs, she expected to learn more about research methods and ways she could use them to help a community organization.

“I wanted to work with external clients and have an experience on what it was like to have someone relying on me to produce timely and informative results to help them make decisions,” said Mueller, who heard about iLabs research through a class presentation by Director Tim Davis.

But she didn’t expect the impact the experience would have.

Working with the Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services (ACCESS), a nearly 50-year-old area nonprofit, Mueller was asked to help create a survey—one that would ask the right questions so the organization could gauge the satisfaction of the people it was serving and make improvements accordingly.

“I can only imagine how hard it is to come to a place where you may not know the language or how the system works. It was awesome to work with an organization that assists with that transition so that people can have a better life here,” she said. “Prior to going to ACCESS, I hadn’t thought about how difficult that transition could be. I wanted to do whatever I could to help.”

She went to the main branch of ACCESS—there are 11 Metro Detroit locations—at various times and days to get a diverse brand sample size. She met with people who were using the different services—like a translation office, a health clinic or children’s center—and had to demonstrate positive body language to help break language barriers for people to feel comfortable in participating in the bilingual survey.

The survey’s findings? People were satisfied overall with the services, with a few recommendations made, which included starting to shift services to accommodate second-generation citizen needs, increasing staff during peak times and no politics on the waiting room televisions.

Mueller, an information technology management and digital marketing senior, said the presentation to the Board of Directors went so well that they also requested a follow-up survey with iLabs.

In addition to helping out people in her community and learning from Davis’ business research expertise, Mueller said another benefit came from her research experience—it helped her land a Ford Motor Co. internship and a subsequent full-time job offer.

“When I did my interview, I told them about the research project I did and how I gained leadership skills, research analytics experience, working with an external client and navigating a cultural barrier. I could see how the interviewer’s eyes lit up,” said Mueller, noting the research she did was sponsored by Ford Motor Company Fund’s Community Corps program. “I’ve always wanted to work at Ford. And now, after I graduate, I will.”

Finding answers, looking for solutions

Junior Matthew Fleming saw friends struggle in college because of their financial situation.

Seeing how that difficulty affected their university experience—for example, it was hard for them to focus on school when worried about paying bills—he wanted to find a way to help. Not able to assist monetarily, he discovered another way: research.

Fleming, a sociology and criminal justice major, said the opportunity came after taking courses with Sociology Professor Pamela Aronson.

Learning that Fleming had an interest in research, Aronson shared data collected previously—from 2010 to 2012—from 100 participants in her study, “Breaking Barriers or Locked Out? How Non-Traditional Students Experience College.”

With that data, Fleming gained a leading role in a student-designed research project.

Fleming and Aronson chose to focus on those student participants who were below the 2010 national median household income level—59 of the 100 students. He analyzed their interviews and noted any campus involvement outside of class.

“We already know, and it has been proven in research, that more advantaged students are more likely to graduate. But we don’t know much about what causes some low-income students to succeed and what causes others to drop out. Since this information was collected years ago, we could track how the students did,” he said, noting participants consented to allow Aronson access to their transcripts. “If we could find influencing factors, we could use strategies to help future students finish their degrees.”

Initially, Fleming was surprised to find that the most disadvantaged of the low-income students had the higher graduation rate. But he said when he and Aronson went beyond the numbers, they learned why.

Analyzing the interviews, Fleming and Aronson found that the students who later earned a degree were open about their struggles. They talked about being homeless, needing food or bringing their children to class. They were forthcoming about academic weaknesses and obstacles they encountered and sought out solutions. The students who didn’t graduate often did not seek help and were not as open about personal or academic hardships.

“The graduates who had the lowest household incomes and the most disadvantaged stories were going to do whatever needed to get done and asked for help. They were open about problems they were facing and accepted help,” he said. “The students more often displayed self-efficacy and confronted obstacles.”

Fleming—advised by and co-author with Aronson—recently submitted a paper on this research, “The Factors That Influence Completion and Non-Completion Among Disadvantaged College Students,” for presentation at the 2018 International Sociological Association World Congress Conference and the 2018 Annual Meeting of the Southern Sociological Society. They hope to eventually submit this paper for publication.

He said this is only a sample of student experiences, but he hopes these findings might positively impact struggling students in the future. And Fleming, who plans to attend graduate school, said he sees how the research process will help his next steps too.

“This research experience has given me the tools and the confidence to sort through data, analyze, organize what I’ve found, and write about it academically. These are skills I will need for graduate school and I’m learning them now,” he said. “The better I am at research, the more I’ll be able to contribute to finding solutions.”