The prospect of bringing more renewable energy onto the grid holds a lot of promise for dealing with the challenges of climate change. But an energy system that relies more heavily on solar and wind power also presents some big technological issues — especially once renewables reach a critical mass. The major challenge stems from their fundamental intermittence: If there are unexpected periods where the sun isn’t shining or the wind isn’t blowing, it could cause major disruptions to energy supplies — meaning the always-on reliability of the grid could be at risk.

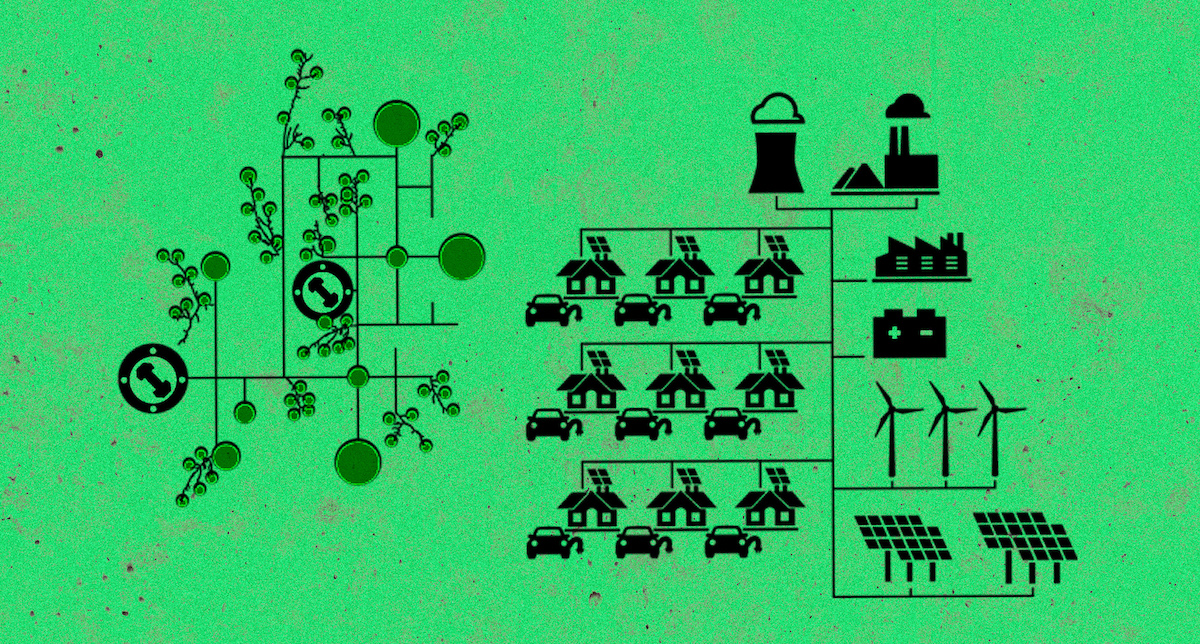

Associate Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE) Wencong Su and ECE doctoral student Fangyuan Chang are among the researchers looking for solutions to big-picture problems like this, one of which is decidedly small. Their latest project focuses on energy “microgrids,” which are pretty much what they sound like. In contrast to the single massive electric grid we use today, where power is produced at big power plants and then sent all over the country, microgrids produce smaller amounts of power that is typically consumed more locally. It’s not an idea that’s complete science fiction. In fact, microgrids are being used today to power everything from data storage centers in Japan to factories in Michigan to several small American cities.

Chang says this surging interest in microgrids is coming from a variety of places. The U.S. military, for example, is interested in microgrids because they offer the promise of energy security and independence. Big manufacturers like microgrids because they allow them to produce more of their own energy — and to do it from renewable sources, which helps corporations with sustainability goals meet their targets. And new interest in microgrids that use DC energy, in contrast to the standard AC energy that electrifies the grid today, is being driven by technological change: Things like solar panels, electric vehicles, electric storage systems, cell phones and computer CPUs all operate on DC not AC energy. Because of this, a microgrid that produced and used DC energy directly, without any need for conversion, would be inherently more efficient.