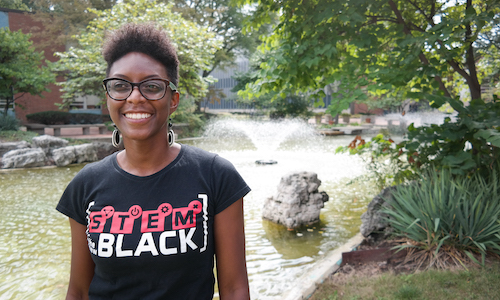

In some ways, DeLean Tolbert’s life at UM-Dearborn looks a lot different today than it did when she was an undergraduate here. For starters, there’s the obvious: Thirteen years ago, she was a student in an intro to engineering course; this semester, she’s teaching it — an experience the second-year industrial and manufacturing systems engineering assistant professor candidly admits still feels “a little crazy.”

But there’s also plenty of continuity to read between those two chapters of her UM-Dearborn story. In fact, the complex research questions Tolbert is wrestling with now — which center on race, engineering skill development and access to higher education — are things she started wondering about when she was a student. The spark came during her senior year, while deep into an independent study with Electrical Engineering Professor Paul Watta. Officially, the project focused on exploring new learning tools for the intro to engineering course; but in the process, she also bumped into some interesting trends and questions about her fellow engineering students.

“Back then I noticed if, say, 10 African-American or underrepresented minority students started freshman engineering with me, just a handful of us would still be around by senior year,” Tolbert says.

And when she pushed a little deeper into university data, she discovered the retention challenges were larger for African-American students. “It, of course, gets you wondering why that is, and if there were things you could do to better support students at key points in their careers, maybe the outcomes would be better.”

She’s still deep down that rabbit hole of inquiry; though today, the platform for investigation is more robust. Tolbert occupies a unique place in the College of Engineering and Computer Science — an engineer who is, by training and curiosity, just as much a social scientist. A case in point is her current research study, which involves identifying the pathways by which students from demographic groups who are underrepresented in engineering disciplines end up studying engineering at the university level.

“For example, one question we’re interested in is the relationship between the students we recruit and the zip codes they come from in terms of technology usage,” Tolbert says. “Detroit is a place where there is very uneven internet access, so we’re interested to see if that could be a factor in whether those students go on to college.”

Mapping such trend lines could lead to new ideas for how to better support students from under-resourced communities. One example Tolbert has been inspired by lately are neighborhood “maker spaces” — creative hubs where kids can “tinker, build, fix and break things.” Having more opportunities like that, she said, could help ignite students’ interest in engineering early on.

Such ideas almost prompt provocative conversations about what “counts” as an early engineering experience. Traditionally defined, that might include things like participation in a robotics program, activities that are common among students from better-resourced communities.

“But what if you’re fixing the lawnmower with your grandfather? Or helping your mom pay the bills? That requires a lot of math and critical thinking,” Tolbert says. “Those are valid experiences too, but we need to encourage students to see them that way.” On the institutional side, she said, that could also mean exploring reforms to admissions policies at engineering schools, so that they’re more inclusive of different types of experiences.

Tolbert knows those are larger college-level, even institutional-level, conversations. But her deep dive into these questions fits right into the current push to make the College of Engineering and Computer Science a more inclusive space. In the past six years, under the leadership of Dean Tony England, the percentage of women students enrolled in the college has climbed from 11 percent to 19 percent, while the number of women faculty shot up from just two to 11. And the college’s near peer mentoring program is connecting UM-Dearborn engineering undergrads with middle and high school students in under-resourced metro Detroit schools. It’s a big part of the reason CECS took home the University of Michigan’s Rhetaugh G. Dumas Progress in Diversifying Award last year.

As Tolbert contributes to those larger efforts to reshape the college, she’s also doing what she can now in the classroom. One of her first-week exercises for students in her intro to engineering course is filling out a personal questionnaire, which helps her build more diverse student teams. Then, she chases that with a lecture about how cultural bias can influence engineering and design on a very basic level.

“I share with them the example of bathroom soap dispensers that had sensors that wouldn’t activate with darker skin on the backs of people’s hands, but would when they flipped their hands over to expose the lighter-colored palms. Or the Ford Windstar, which didn’t sell well until it was redesigned by a team of women engineers to meet women’s needs that were ignored in the previous design. That’s intended to show the students that this is not just a justice or an equity issue. It demonstrates that we do engineering poorly when we don’t have many voices at the table.”