Associate Professor of Bioengineering Amanda Esquivel has lost count of the number of middle schools she’s been to over the years in an effort to get young people excited about STEM subjects. She finds that right-sizing an activity is definitely key to a school visit. On the one hand, the demo or experiment has to be big enough to get students interested. On the other, it has to be small enough that it’s manageable to pack up and set up without too much fuss. Recently, however, a pandemic hiatus from her typical rhythm of school outreach got her thinking, what if she flipped the script? What if instead of coming to them, she brought students to an actual engineering lab on campus to experience the real thing, not some backpack-sized approximation?

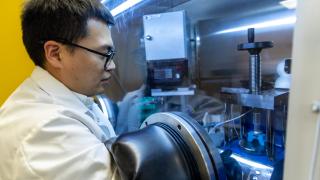

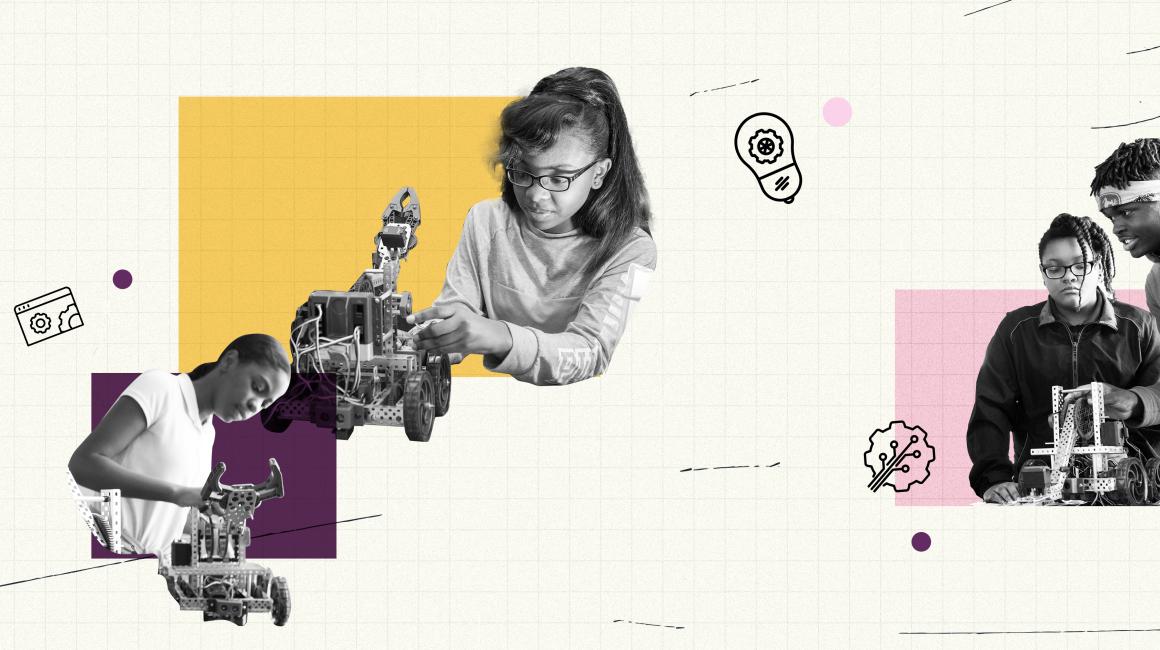

Last month, Esquivel gave it a shot — and got her colleagues in on it too. In early May, about 40 students from Detroit’s U Prep art and design high school and its STEM high school came to campus for an entire school day. They got to hang out with the UM-Dearborn rocket and racing teams, picking their brains about how the student clubs work and the complex things they get to design and build. Human-centered design engineering faculty DeLean Tolbert Smith and Sarah Nesbitt led an activity where students got to deconstruct and then redesign a pair of eyeglasses. And then they headed into the labs. Esquivel got eight different engineering faculty to open up their labs so students could get their hands on actual instruments, see how math and science skills are used to solve real-world problems, and chat about how undergraduate and graduate students contribute to research. In Esquivel’s own lab, where she studies sports-related injuries, she outfitted the students with wearable sensors and had them use formulas and the data they collected to calculate jump height. “It’s great when you go to their schools and talk, maybe show a video of the lab, and do an activity,” she says. “But it really can't compare to inviting them to our campus and showing them in-person the high-tech equipment we use — or letting them actually touch it.” Coming to campus, she says, they simply got a much better look at what engineering students actually do. Better yet, the students seemed to think it was all pretty cool.

Hosting the U Prep students, who were mostly African American, is indicative of how UM-Dearborn engineering faculty, and the college in general, are upping their outreach game when it comes to demographic groups that have been historically underrepresented in engineering. Part of the reason is that at most universities, including UM-Dearborn, gains have been slow and steady more than transformative, says Tolbert Smith, whose research focuses on STEM’s equity gaps and improving access to STEM education. Here at UM-Dearborn, for instance, women now make up around 24 percent of engineering students, which CECS Dean Ghassan Kridli notes has increased steadily over the past decade and is above the national average of 18 percent. But it still lags our overall enrollment demographics: at UM-Dearborn, women make up just under half of full-time students. Among Black students, there’s even more ground to make up. “We’re also ahead of the national average, which is closer to 3 percent, and we’re at 4.5 percent,” Kridli says. “But it doesn’t represent the composition of our area. Almost 70 percent of our students are from Wayne County, and Wayne County is about 38 percent African American. So there’s a big opportunity for us to be doing much better.”

Tolbert Smith notes this is hardly a challenge that’s unique to UM-Dearborn. “Honestly, I think people across the nation who work in this area are a little frustrated, because we’ve been putting a lot of resources into diversity, and we’re not seeing the outcomes that we thought we would given all the money that’s being spent,” she says. “And this is broadly across academia and industry. It’s not that there’s been no impact, it just hasn’t been a mass change. So people are trying to figure out, what is it we’re doing that’s working, and what do we need to alter about our approach?” Within higher education, Tolbert Smith says efforts over the past decade have commonly centered on two themes: scholarships and outreach. The logic of the latter is that because of historical biases in engineering fields, many women, Black and Latino students may simply not envision engineering as a possibility for their own lives. By introducing students to STEM at an early age, and showing them all the cool things engineers do, we can expand the horizon of possibilities they start dreaming about. Or so the argument goes. But Tolbert Smith says an emerging body of research is showing that while this may be a necessary condition for transforming enrollment in STEM programs, it’s not proving to be a sufficient one. To really start taking larger bites out of these enrollment gaps, we need to do more. More importantly, we need to know what additional actions are actually going to be effective.

Tolbert Smith says, here again, recent research can point us to some next steps. For example, one of the big factors in whether students decide to enter and stick with an academic program is whether they feel like they belong there. And this, Tolbert Smith, hints at ways engineering departments can change their cultures to actively value students from diverse backgrounds. For example, in just about any intro engineering class, faculty are likely going to talk with students, either formally or informally, about careers in the field. “But if we’re only introducing them to fields that have historical biases towards men, that might not resonate with a female student, and she might start to feel like ‘if this is what engineering is, then this is not a direction I want to go.’” Another example: Tolbert Smith says a few years ago, when UM-Ann Arbor noticed declining female enrollment in its engineering programs, they created sections of courses that dealt, in part, with social issues. Women disproportionately chose those sections over the traditional ones.

Tolbert Smith says another aspect of belonging is faculty validating a more diverse set of engineering experiences that students are bringing to the table. Robotics teams, for example, have become the dominant form of pre-engineering experience among high school students, and college faculty are often directly engaged with these kinds of programs as advisers and coaches. As such, there’s familiarity with that paradigm. But let’s say a student’s interest in engineering was ignited by a less formal experience, like, building custom, small-engine mini bikes (a big thing in Detroit), or building or fixing things with a parent or grandparent. Tolbert Smith says that’s a totally valid pre-engineering experience that’s going to help a student develop a lot of knowledge and skills, but a faculty member may not always recognize it as such or know how to value it because it’s outside the scope of their own experience. Similarly, Kridli says the new emphasis on project-based learning in the college offers an opportunity to build class curriculum that comes directly from a student’s own experiences. “Through course projects, we could actually give the students agency to design solutions for problems that come right of their own neighborhoods or communities — rather than academic problems that come out of a textbook,” Kridli says. Conversely, Tolbert Smith says faculty can tune into things that may trip a student up on their engineering journey. For example, she recently had a young woman student who was nervous about using some of the big tools in the MSEL machine shop. “So I reached out to Shawn Simone, the MSEL Assistant Director, and he offered to work directly with her. Shawn’s extra attention gave her a path to overcome her fear.”

"Honestly, I think people across the nation who work in this area are a little frustrated, because we’ve been putting a lot of resources into diversity, and we’re not seeing the outcomes that we thought we would given all the money that’s being spent. It’s not that there’s been no impact, it just hasn’t been a mass change. So people are trying to figure out, what is it we’re doing that’s working, and what do we need to alter about our approach?"

In addition to making students feel like they belong in engineering, we may also need to be reaching them at an earlier age. Many outreach programs have focused on high school students, but Kridli says, in some ways, that’s a bit late. Reaching them in middle school isn’t just about getting to students at an age when they’re starting to develop their long-term interests, though that’s part of it. It’s also a practical matter of academic preparation. In terms of math, engineering programs use calculus as the foundation for their courses. And typically, seventh grade or so is when students get started on a sequence of math courses that will determine where they’ll end up by the end of their senior year. If a student who has an interest in engineering isn’t enrolled in the proper math course in 7th grade, they might only make it to trigonometry by 12th grade, which leaves them with a lot of ground to make up once they get to college. Because of this, Kridli says making sure kids who are still years away from college are on the right track is crucial. Similarly, Tolbert Smith sees a lot of opportunity to forge tight, mutually supportive relationships with specific majority minority schools in the area, similar to how UM-Dearborn’s Education department has developed trusted partnerships with area districts and administrators when it comes to practicums and student teacher placements. "We have a shared interest: Teachers want to make sure their students can achieve everything they want to, and once they get to college, we obviously want them to succeed too," she says. "So I think one thing we can start with is simply asking teachers and schools what it is they need to better prepare their students for college and get actively involved in helping them do it.”

Tolbert Smith says one of the other missing ingredients is “intentionality,” particularly when it comes to recruitment of Black students. Both she and Kridli believe that one of the reasons we’ve had more success boosting enrollment among women students compared to Black students is that our strategy has been more organized, more goal-oriented, and has been in place for a longer period of time. “Years ago, when Dean England came in, he set a specific goal to hire more women faculty, and I believe that’s one of the reasons why I’m here,” Tolbert Smith says. “The college was even given an award by the main campus for their work in this area. They set a goal, they changed the way they recruited, they changed the interview and screening process to deal with bias, and we got results. So I think we could follow that same playbook when it comes to Black students: We could set some goals, and then be really intentional about the steps we’re taking to reach those goals.” Kridli also notes that as the college has hired more women faculty, they’ve seen a proportional increase in the number of women students.

In general, Kridli says one of the big realizations of the past several years is that successful recruitment of students from underrepresented groups can’t be conceived as a single point of contact, like a scholarship or an outreach event that hopefully ignites someone’s engineering journey. Rather, it’s more like a long drawn-out chain of events, built over years, with each link in the chain being critical to the outcome. For sure, outreach will always be crucial, because it’s often the thing that introduces a student to STEM. But if the student isn’t then getting the proper academic counseling in middle school, and therefore not getting into the right math class; or if their math teacher feels like they need some exciting new classroom approaches; or if a student gets to college and they don’t feel like their instructors get their experience, or their classes don’t leave them feeling invested, then the chain could break and their pathway to a career in engineering breaks down with it. Kridli says the college is now investing in all of these areas. For example, in a few weeks, a group of eight faculty are heading to Massachusetts for some training on approaches to project-based learning. Faculty teams from the Mechanical Engineering and Industrial and Manufacturing Systems Engineering departments are collaborating on a grant focused on culture changes within these departments. And Kridli says the college is building out a strategy for how to work more closely with middle and high schools, their academic counseling staff, and even parents, so that students can get on the right track at this crucial time in their lives.

Humility will also be part of building a college that looks more like the region. Kridli says that if this were an easy challenge to solve, then someone would have done it and we could simply follow their lead. Instead, we have to be innovators. Tolbert Smith’s guess is that many of the new actions we’re now taking — even if they prove to be effective strategies — could still take a decade or more to really pay off. “I think we’re reaching a moment where we’re facing the facts that because of racism, because of unequal resources, because places that pay higher taxes get better schools, there are going to be challenges — and we have to commit to being a part of addressing that,” she says. “Of course, these are broader problems in society. But if we truly want students who live in communities where these gaps exist, I do think, as a public institution, we have to be willing to do this work. And I am hopeful that if we put in an intentional effort, we can see enrollment and graduation rates improve amongst communities of color in CECS.”

###

Story by Lou Blouin. Graphic by Violet Dashi.