For students, this experiential learning and networking is transformative. And that’s not just a buzzword. It’s backed by data. New alumni, on a campus made up of nearly 40 percent first-generation undergraduate students, start their careers with the fourth-highest starting salary of all Michigan public higher education institutions.

Wolverine undergraduates are given the opportunity to stand out. One of those ways is through a U-M research initiative called Mcubed — aptly named because each research project brings together three faculty members from the three University of Michigan campuses.

UM-Dearborn faculty members and their student research assistants are taking part in 33 Mcubed research projects, which explore special education needs, cultural preservation, cell regeneration and more. It’s this consequential research that supports these experiential learning and transformational statements — along with advancing technological innovation, democratic vitality and the promise of opportunity.

Enlisting nanoparticles in the fight against pediatric traumatic brain injuries

UM-Dearborn senior Samiha Ishrat recalls being told that bumps and bruises are a part of childhood play and exploration. Falls are lightheartedly included in favorite kid songs and nursery rhymes.

But science is showing that the effects from seemingly routine tumbles aren’t as benign as believed: Traumatic brain injury is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide — more than any other traumatic insult. And it affects more than 1.7 million Americans each year, with children birth to age four at the highest risk.

That’s not something to sing about.

Working with Assistant Professor of Neurobiology Zhi “Elena” Zhang in the research lab to discover ways to rescue cell loss affected by head trauma, Ishrat, a biology major, listens to why this is a concern.

“Children this young may not be able to tell you something is wrong. Many times they get back up and keep playing as if nothing serious has happened,” said Zhang, whose research focus is neuroplasticity in learning and memory. “But, as they get older, we may see learning disabilities and emotionally erratic behavior tied to these falls and bumps that cause pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI). If we can prevent and reverse the progression of the injury while their brains are still developing, they may avoid delays or erratic behaviors associated with TBI.”

"Children this young may not be able to tell you something is wrong. Many times they get back up and keep playing as if nothing serious has happened.” — Zhi “Elena” Zhang, assistant professor of neurobiology

Zhang, whose interest in this research area strengthened when she was pregnant with her first child, said there is a way to reverse the brain damage. Through her previous research work at Johns Hopkins University, there are several medicines that are proven to work in a lab — essentially they can reduce neuroinflammation and excitotoxicity, allowing for improved memory and function — but putting the procedure into practice is another challenge.

“We didn’t find a cure for those longlasting effects from TBI. That’s because the majority of the drugs cannot pass the blood-brain barrier, which is what separates the blood from our brain tissues to protect our central nervous system,” Zhang said. “However, nanoparticles can cross the blood-brain barrier. So we want to see if we put the drugs on the nanoparticle, will it go to the target cells? And, if it does, will the drug be active once it crosses the barrier? I needed experts in other areas to help with this.”

Filling the Gaps

So Zhang started an Mcubed project — targeting endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and restoring ER homeostasis in pediatric traumatic brain injuries — hoping to find a cell biology and a nanotechnology expert to fill in research specialty gaps.

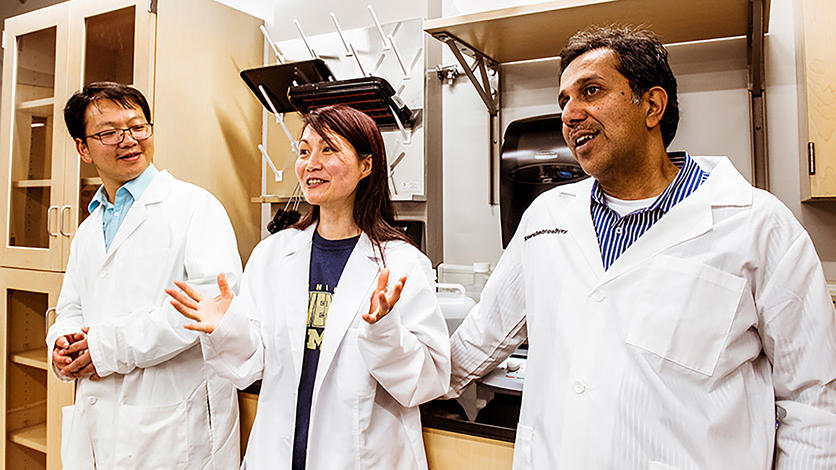

Today, Zhang, Professor of Chemistry Krisanu Bandyopadhyay and U-M’s Guojun Shi, a research investigator of molecular and integrative physiology, are working together with nearly 10 UM-Dearborn undergraduate students to find a way to get effective medicine across the blood-brain barrier.

“This research challenges me to think differently,” Ishrat said. “You think outside the box, explore different paths in your search, expect the unexpected and be resilient regardless of negative outcomes. These are some essential qualities that are not only crucial for a researcher, they are also important when navigating through life.”