Forty-two-year-old Quan Neloms counts himself lucky that his childhood overlapped the Golden Age of Hip Hop. Make a movie based on his teenage years growing up in Detroit in the ’90s— which by the way, he’s working on a screenplay for — and you’d see a lunchroom full of kids pounding out beats on tables and friends circling up in groups to rap or beatbox until the bell called them back to class. After school, the venue would switch to the Hip Hop Shop, a Detroit clothing store where Neloms and his friends came of age at Saturday open mics with J Dilla, Eminem and musicians from the D12 collective, before these artists were known to national audiences. One of his favorite, and embarrassing, memories from his childhood was the time Proof and Bizarre from D12 called out Neloms and his friends during a rap battle, at which they had just planned to be spectators, bobbing their heads while the “gladiators” did the work. The shy 15-year-olds melted at the invitation to freestyle. “We don’t know how to rap, man!” they pleaded. Which wasn’t true. Neloms had started writing rhymes and rapping when he was 14, and he was actually pretty good, especially at the writing part. When he was 17, Jason Wilson, the DJ from the Detroit rap group Kaos & Mystro, invited Neloms and his friends to record in their studio, which turned out to be something of a turning point in his life. Not because they ever got a big record contract. But because hearing that his voice actually sounded good gave a shy kid a newfound confidence that bled through to the rest of his life.

Neloms, a veteran Detroit educator who’s been a lecturer at UM-Dearborn since 2021, likes to joke that his early studio experience made him the first member of Lyricist Society, the after-school group he started in 2009 when he was a high school teacher at the Douglass Academy for Young Men in Detroit. On one level, the mission of the group is to do more or less what that producer from Kaos & Mystro did for him. Typically, the Lyricist Society process starts with the students discussing subjects, writing rhymes and laying down some foundational instrumentals, which they workshop as a group until they feel a track is ready to record. Then they hit the studio, aided by a professional producer who volunteers with the group. They also make music videos, which the kids shoot and edit. The body of work Lyricist Society has produced over the years, which you can view online, is honest, smart, often funny, and frequently rooted in history and social issues, a flavor that Neloms, who worked for years as a social studies teacher, is no doubt partially responsible for. Try not to fall in love, for instance, with “Nutrients,” an ode to eating well inspired by the kids’ experience with Neloms’ former classroom neighbor, Marquita Reese, a math teacher/farmer who ran the school farm at Douglass for many years. Rounds of the playful chorus, I love my nutes, gimme some good food, sung just a little off-key, à la Biz Markie, are interwoven with a sweet scene of a mother and son enjoying food together, plus critiques of GMOs, McDonalds and the obesity epidemic. At the end of the track, a sample of some 1969 footage from the Black Panthers’ school lunch program eases in, as the sweet Grant Green-style electric guitar licks play us out. It works because it’s complex, funny, sincere and well-produced. Most of all, nothing feels obvious. “One of the things I really try to help them understand is that you don’t need to sell yourself short talking about the same three things that people stereotype hip hop for,” Neloms says. “You have your own thoughts and experiences. That’s what makes you original. Say that, and people will want to hear what you have to say.”

Creation is obviously crucial to the Lyricist Society process. But Neloms is just as big on the showcase. The idea of helping kids “find their voice” can easily slip into cliché if you don’t have a method. For Neloms, making the music is step one of the Lyricist Society process. Step two is taking the risk of sharing it and getting a chance to experience what it feels like for others to be interested in what you have to say. After their recording phase is complete, they often do live performances, attended by friends and family, where the kids invariably surprise, impress and get smothered with love. When they post the songs and videos to YouTube or social media, the comments sections blow up with positive feedback. Neloms says the kids really started taking him seriously when one of their videos won a Michigan Regional EMMY, just one of several honors they’ve racked up over the years. “Nutrients,” for example, became the anthem played during breakfast at several Detroit schools. U.S. Senator Debbie Stabenow even used it to help promote a nutrition initiative. Now, when the local or national media reach out for an interview, which happens fairly regularly, Neloms says the kids do most of the talking.

* * *

If Neloms’ early recording experience is one parent of Lyricist Society, his Detroit public schools social studies classroom is the other. Neloms started teaching fresh out of college, and although the 22-year-old had strong mentor teachers, the challenge of running a classroom presented a steep learning curve. It was also a tumultuous time for public schools in Detroit. Not having enough books for every student, the shorthand for the city’s lack of resources during that time, was a reality in his social studies classroom. So Neloms looked to his love of hip hop partly as a way to bring new material into the classroom, and partly as a way to connect with his 8th graders, who were, in terms of their musical tastes, still more or less his peers. He translated the heady historical debates between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton and Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois into battle raps, performing both parts, cracking the kids up in the process. He’d go digging through his musical library and find tracks relating to just about any social studies topic: Lupe Fiasco’s “American Terrorist” for the unit on Westward expansion; Jay Z’s “99 Problems” for a discussion on the Bill of Rights and the 4th Amendment. He’d use the songs as a leaping off point for class discussions, putting the lyrics up on the board, analyzing, annotating, asking the kids to offer their take on what they thought the artist was talking about and how it related to what they were learning. One of his go-tos was an original rap he wrote called “Potential and Possibilities,” a call-and-response with the kids that affirmed them and the purpose of their education. Last year, when he ran into one of his students from that era, who’s now in her mid-30s and owns her own business, the introductory shouts of “Mr. Neloms!” were quickly followed by a spontaneous rendition of “Potential and Possibilities.” He wasn’t so shocked she remembered the hook. But the fact she nailed all the lyrics without hesitation showed just how much had stuck.

Explicitly validating the value of learning, being creative and geeking out about your interests, no matter what they are, is foundational to Neloms’ approach, largely because it’s a message that greatly influenced the trajectory of his own life. Growing up, Neloms had always been a good student and, at the end of 8th grade, he tested into Cass Tech, one of two competitive magnet high schools in Detroit. But it was a rocky transition. The 8th grade class in his neighborhood school numbered about 20; at Cass, he was one of about a thousand 9th graders. Surrounded by good students and searching for an identity, he decided he didn’t want to be “one of the smart kids.” He took inspiration instead from his favorite hip hop group at the time. “I’d walk into Cass with my skull cap down, thinking I’m Wu-Tang, and I spent more time cultivating that image than I ever did studying,” Neloms says. “I was basically an in-school drop out.” Sometimes when he’d skip class, he’d go to study hall and write rhymes. But it didn’t help his GPA, which was a .896. That summer, he got a letter from Cass stating he wasn’t being invited back sophomore year.

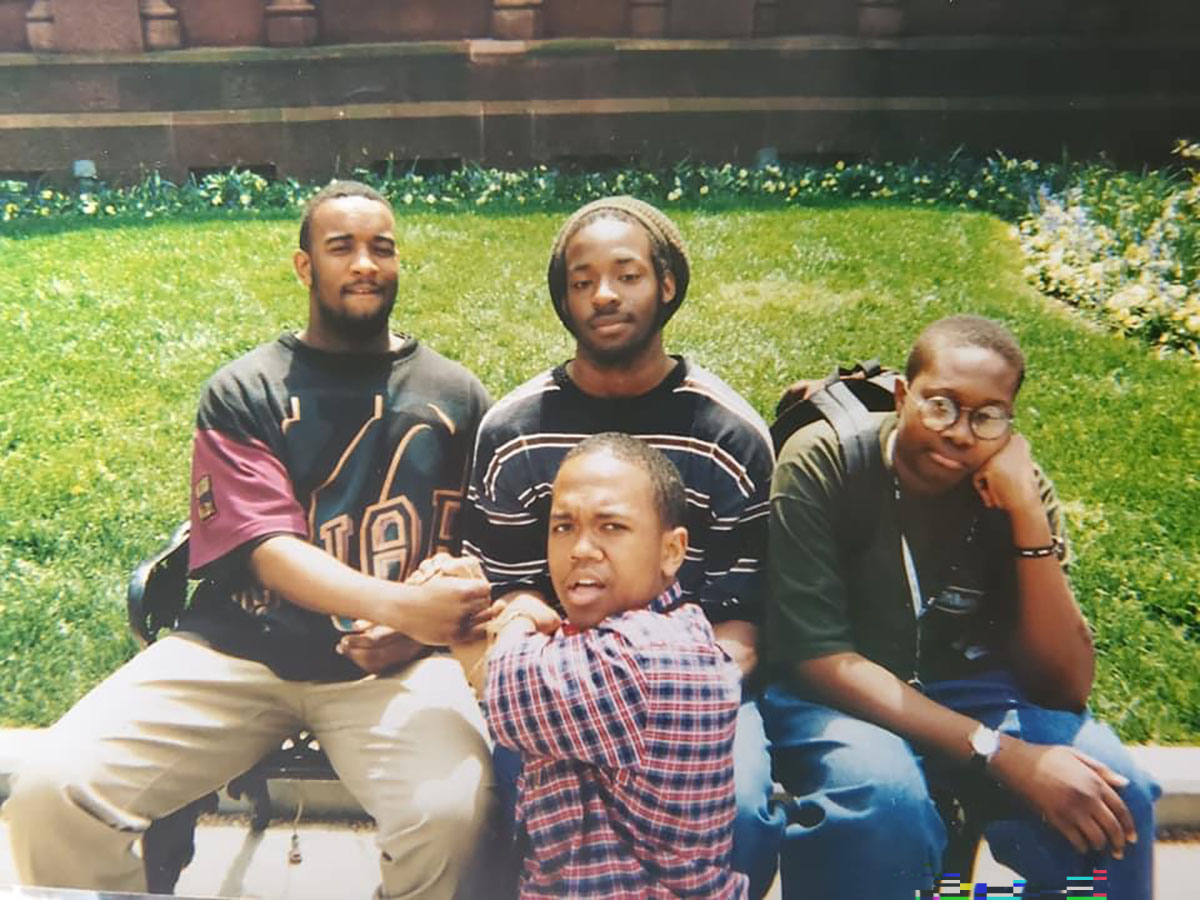

Ask Neloms what turned things around and he’ll warn you of the trip down memory lane that’s about to hit you. The way he talks about the group of male friends he met the summer before 9th grade reminds you just how crucial friendships can be, especially when you’ve endured a prolonged bout of adolescent loneliness. A few years prior, Neloms’ family had moved from a kid-filled apartment building on the east side of Detroit to a west side neighborhood that was mostly seniors. For three years, he floundered. “I mean, it was bad. I’d go outside and play with bugs. I used to pray at night for friends,” he says. One day he took a walk and decided to cross Puritan Avenue, the border of his neighborhood, and discovered all the kids were living on the other side of the street. In particular, the physical juxtaposition of two young men about his age caught his attention. One guy stood over 6 feet, with long dreadlocks and a muscular physique. Next to him walked his friend, who was a little person. A few hours later, he noticed the same pair walking on his side of Puritan, and the desperate Neloms jumped off his porch and got right to the point: “Hey wassup, y’all. You live down there, right? Hey, man, I don’t know nobody. Would y’all be my friends?” When Ferris, the big guy, and Ivan, his buddy, looked at each other and said “sure,” Neloms felt like his prayers were answered.

Ferris, Ivan, and their friends Damon and Lamar, whom Neloms would meet soon after, weren’t like anybody he’d met before. Ferris was super into working out and never got anything below a 4.0 in school. Lamar was the artist of the group. Two of the guys studied a dancelike Brazilian martial art called capoeira, which they even got paid to perform from time to time. They all loved hip hop and wrote their own music. “Here was this group of guys that rap, they can fight, they’re strong, they’re smart. I mean, they were Renaissance men,” Neloms says. “And I was inspired by them. But more than that, I realized I was like them. Before that, I was so caught up in this identity thing where I thought I had to be a thug. I thought I had to be like some of the stereotypical portrayals of Black men found in some hip hop music. But with these guys, it wasn’t like that. You could still be yourself. You could embrace your inner nerdom and still feel good about yourself. Achievement was cool.”

Neloms says, more than anything, that nerd ethos is what colors the vibe of Lyricist Society. Culturally, hip hop isn’t typically associated with nerds. But Neloms argues the fact that there’s no formal place for it in the school curriculum means the kids who might be interested in making music aren’t all that different from the early internet geeks of his ’90s upbringing. “There were a lot of kids who were interested in music and art and stuff, but they weren’t interested in being in the band or in the drama club,” Neloms says. “So we created a place where that kind of comradery could happen. They get the T-shirts, they get the hoodies that say Lyricist Society. And they walk down the hall, just like the basketball players with their letterman jackets. It’s a symbol that at school, my interests are considered important. And they have the uniform and the trophies and the highlight reels to prove it.”

* * *

Neloms is a relative newcomer to the UM-Dearborn campus, having begun as an instructor for the social studies methods course a few years ago. He was recruited by Education Professor Julie Taylor, who for years hosted Neloms as a guest lecturer in her courses, where he’d talk with teachers in training about the integration of music into social studies education and its impact on his students. When a lecturer spot opened up, Taylor encouraged Neloms to apply and he’s been part of the education faculty since. Recruiting part-time faculty like Neloms, who have full-time day jobs and may only teach a class or two at the university each year, is crucial to the educational philosophy of the department. In particular, Taylor sees people like Neloms, who are using creative teaching strategies, as being part of the vanguard of educational innovation. In fact, Taylor has co-authored multiple academic articles featuring Neloms’ and his former Douglass colleague Marquita Reese’s work, focusing on the pedagogy behind their creativity.

For sure, having logged 20 years as an educator, including the past few in which he’s transitioned to being a school counselor, Neloms has plenty to offer at the university level. But as an instructor, he prefers to be a “guide on the side” rather than a guy who’s seen to have all the answers. He operates his UM-Dearborn classrooms much the way he does Lyricist Society, with open-ended discussions of ideas designed to help students reckon with complex material and discover and articulate their own perspectives. Given that many of his students are, like him, practicing educators with years of experience, it’s an approach that makes sense. “You hear a lot of people say college is where you learn everybody else’s theory and everybody else’s research, and you lose yourself in it,” Neloms says. “I want them to find themselves in it. I want them to blend the theory with their own perspectives and experiences in a way that makes sense to them. If they take away anything from my course, I want it to be that education doesn’t have to be rote. It can be a passion-filled, creativity-filled endeavor.”

Helping a teacher find their particular voice can be significantly more challenging than lecturing on the latest theory. It certainly helps that Neloms is basically a living example of how it can work, and he can talk in methodical detail, complete with PowerPoint slides, about his own journey of using hip hop as an educational scaffold. Going forward, Neloms says he’s starting to think more about how he can add more show to the tell. Specifically, he’s been brainstorming a series of field trips designed to introduce students to less conventional methods that they might be able to incorporate into their own teaching. For example, he’d like to take the class down to the Dequindre Cut, an old below-grade railroad line running through the east side of Detroit that was converted into a pedestrian and cyclist path back in 2008. In more recent years, it’s become known for its increasingly elaborate graffiti, which covers many sections of the tall concrete walls on either side of the cut. Neloms sees the work not only as significant pieces of art, but as sharp social commentary, storytelling and conversations between the artists, many of whom are young people. Also on the field trip agenda: an open mic event in Detroit. While open mics are typically associated with performances of music or poetry, Neloms sees them as a highly adaptable format for showcasing student work of any kind, which he sees as an indispensable part of validating student voices. “But there’s an art to running a great open mic,” he says. “So I want students in the class to see how the pros do it.”

Now two decades into an already impactful career, Neloms can be considered one of the pros himself. Though many of his methods are born from his own interests and experience and sharpened through iteration, it’s worth noting that his general approach has increasingly found validation in the education world. For example, a gamified curriculum called Rhymes with Reason, developed by one of Neloms’ professional acquaintances Austin Martin, uses a close study of hip hop lyrics to teach vocabulary. When Neloms had the students try Rhymes with Reason in his own classroom, he saw their test scores more than double over the course of just a few weeks. And within his own informal experiments, there’s no more validating and satisfying set of results than the growing ranks of Lyricist Society alumni who have gone on to college, many to pursue careers in education or the arts, building on skills they learned in the club. It’s not surprising that many of them regularly drop in on Lyricist Society meetings to mentor the generation coming up behind them.

In many ways, that’s just adding a layer of proof to a truth that Neloms started figuring out when he was a young person himself: If you’re a nerd about something, and you can work up the nerve to show people your real self, it can be a means of opening up an electric point of connection between people. Passion being contagious doesn’t always mean that everyone has to like exactly the same things. It’s the sincerity that’s contagious. It’s the idea that using your voice can help someone else find theirs.

###

Story by Lou Blouin